The women of the Padaung tribe, a Shan term meaning "long necks", can be found in Burma, in the Loikaw region (Kayah State), or in Northern Thailand in the Mae Hong Son region, very close to the Burmese border where this minority fled in 1988. [1]. But who are these long-necked Venuses that only a few explorers and adventurers were able to meet during the 20th century and have been parked in five villages and reduced to the status of a tourist attraction.

They wear brass spirals around their necks and smile at strangers. As soon as a group of tourists arrives, they bustle around their bamboo stalls displaying handicrafts. They are obliged to smile and kindly allow themselves to be photographed. These women, whom some tour operators include on their itineraries, are the "long necks" of the Padaung ethnic group, a sub-group of the Karenni (or Kayan) people of Tibetan-Burmese origin. Confined to villages guarded by the Thai authorities, these refugees live in these camps all year round with their children, spouses and elderly parents. Without legal citizenship, they have limited access to infrastructure, healthcare and education, as local schools do not offer any education beyond sixth grade. Without identity papers, they cannot move freely beyond the town of Mae Hong Son.

Fair attractions

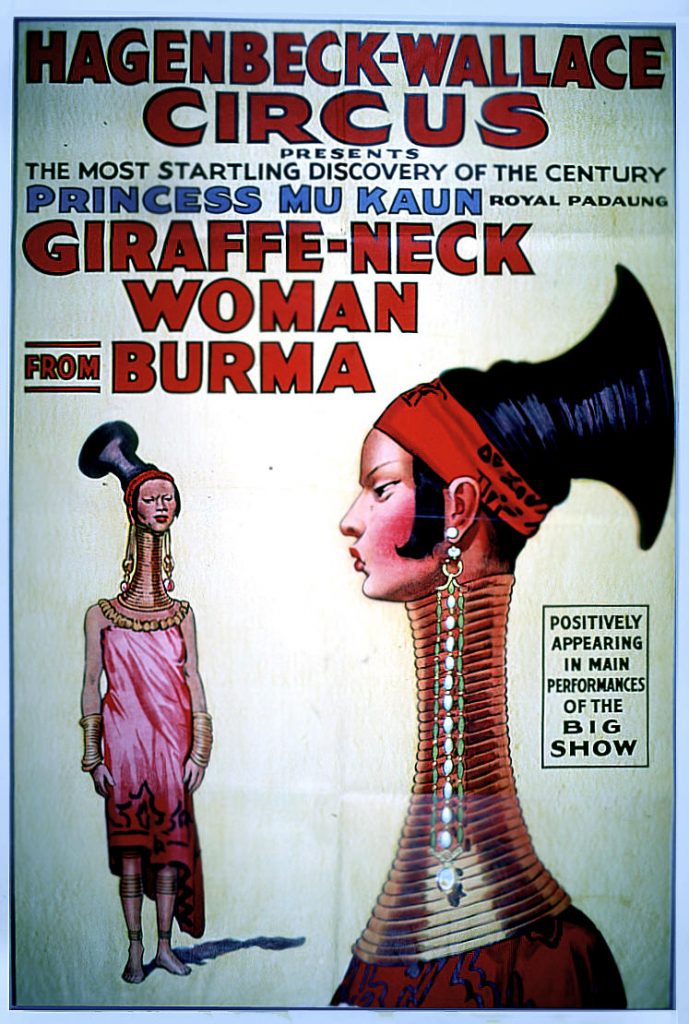

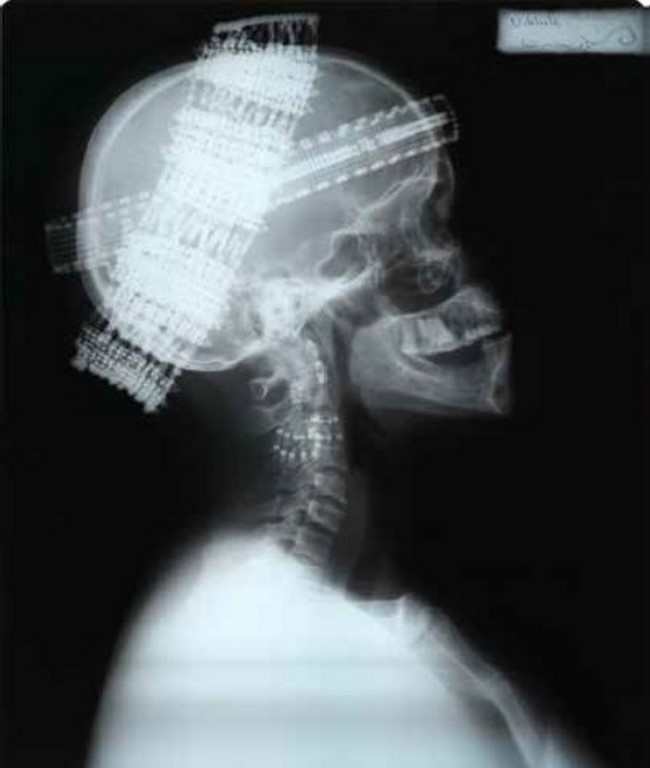

These women, with their necks and bodies encircled in copper or brass, have been curiosities since the 1930s. Discovered by explorer Sir James George Scott (1851-1935), a journalist and adventurer who helped establish British colonial rule deep in the tribal lands of Burma, these women have been exhibited many times locally at fairs and festivals. They were even sent to circuses in the United States and Europe, including the Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus in 1934, who named them "giraffe women".[2]After the Second World War, a number of travellers and anthropologists began to take an interest in these virtually unknown tribes living in the jungles of the Burmese mountains. From 1955 to 1957, the Franco-Polish explorer Vitold de Golish (1921-2003) led a hundred-strong expedition to meet the Nagas and Kayan tribes. He discovered the women of the Padaung tribes belonging to the Kayan Lahwi ethnic group. They live in small villages on the plateaus overlooking the Salouen valley.[3]He woke up to find them lying on a bamboo platform in the hut where he had been invited to spend the night by the village chief, all leaning over his mat and staring at him in amazement. "These heads swayed gently at the end of oversized necks 30 to 50 cm high (He's exaggerating a bit too much...). They were encircled in copper from head to toe: their necks, arms, legs, feet and sometimes even their stomachs were surrounded by gleaming spirals. His book Au pays des femmes girafes made them famous beyond their borders, stimulating the curiosity of journalists and photographers. But in 1962, the Karenni rebelled against the dictatorship of Burmese General Ne Win. Loikaw, the capital of Kayah State, and the surrounding area were henceforth off-limits to tourists. The only way to get there was to enter illegally, which photographer François Guénet did [4] in 1985. With the help of the Karen rebels, he took three young Padaung women wearing the famous brass rings to a small Thai hospital, where he had their necks x-rayed. Surprise: the X-rays revealed that the rings did not lengthen the neck; rather, they pressed on the collarbones and ribcage.

The tiger legend

But why this strange practice that is supposed to stretch the neck? The origin of this ancient tradition remains unknown, and many legends have circulated about it. One of them, recounted by Golish, tells of how women used to wear gold rings to protect themselves from tiger bites when working in the forest, as revealed to him by a tribal chief. This protection then became an ornament synonymous with wealth and an attribute of feminine beauty for the Kayan, even if today brass has replaced gold. Jérôme Kotry, a specialist in Burma and South-East Asia, argues that "the origin of such a practice undoubtedly lies in the desire to protect Kayan women from abduction and rape by the dominant peoples of the plains and plateaus. Wearing these spirals made the women less attractive". However, although this tradition is declining, some women, and not just the older ones, continue to wear it and cannot imagine feminine beauty without a long, beautiful neck. There was even a time when it was impossible to find a husband without this metal ornament, as its height symbolised the wife's dowry. For this reason, women endured the discomfort and injury that this heavy necklace could cause.

Up to 10 kg of metal

Traditionally, little girls receive their first necklace, a spiral of around four or five rows, at around the age of five. Before this, their necks are massaged with ointments and stretched in a ceremony that usually takes place on a full moon day. The shaman first consults the omens by examining chicken bones to determine an auspicious day. It is an elderly woman, a "witch or medicine woman", says Golnish, who installs the first spiral. During the ceremony, the girls also receive silver bracelets and a spiral of several turns installed under each knee. The rings are made from coiled brass wire, about 1.5 cm in diameter. Depending on the girl's growth, the neck spiral is removed every two to three years and replaced by a longer specimen. Around the age of 15, a shoulder spiral with four to six turns is added to reinforce the illusion of length. At the time of marriage, her total height can reach 20 to 25 cm and a weight of 10 kg. Every morning, the women have to wash it carefully and polish it to remove the verdigris caused by sweat and damp. These singular ornaments are heavy to wear and very restrictive in everyday life: the women can only drink through a straw, they cannot bend their heads, they need help with their grooming, they sleep with their necklaces on and cover their necks with leaves to prevent chafing and sores. While these adornments were once the pride of the Padaung women, they are now their prison, and some young girls are taking off their necklaces to protest against their captivity in Thailand. Contrary to what has been said many times, removing their necklaces is in no way fatal.

« Stop the Human Zoo »

In 2008, UNHCR[5] has encouraged a boycott of tourist visits to Kayan refugee villages. Before the Covid pandemic, a few thousand tourists, many of them American and Chinese, came each year to see these exotic beauties, without really realising that these women were prisoners of a system that forces them to perpetuate a tradition, above all to feed their families. Many of them hoped to leave these villages with the help of NGOs for countries like New Zealand and Finland, which agreed to take them in, but until then the authorities were reluctant to let them leave because they brought money into the country. Today, tourism in Thailand has collapsed and the boycott is no longer an issue in the same way. Some have crossed the border again and returned to their native lands, near Panpet and Demoso in Kayah State, forced to work for poverty wages. The regional Minister for Ethnic Affairs declared in 2020 that there would be no aid for returnees. Many of them are therefore waiting for the epidemic situation to improve before returning to Thailand, where they used to earn 20 to 30 baht (between 50 and 80 euro cents) for a photo, plus a subsidy of around 50 euros a month from the Thai government. A sad return to exile for those who dream of freedom and a more humane world.

The Ndebele: Africa's last women-giraffes

The Ndebele are a group of warrior tribes, related to South Africa's two major ethnic groups, the Zulu and the Xhosa (Nelson Mandela was descended from a royal Xhosa family). They forged a strong identity by resisting the Boers. Dispossessed of their land and reduced to semi-slavery on the victors' ranches in 1887 after nine months of war, 80% left to settle in what is now Zimbabwe. The remaining 250,000 were deported to the Transvaal Bantustans and subjected to apartheid. Their art, which is expressed through mural painting and dress weaving, the preserve of the women, has brought to light the incredible architectural and decorative wealth of a people who have kept their artistic tradition alive. Women dress in different ornaments depending on their age and status. After puberty and initiation, they cover themselves with a rigid apron mounted on a goatskin and a loincloth from which rows of pearls hang.

At the time of her marriage, the young bride received from her husband the brass rings, the idzila. She will now wear them around her neck, arms and ankles, as well as a number of pearl necklaces. The idzila expresses a woman's attachment to her home and her husband, and has earned them the title giraffe-women, which they share with Padaung women.

Karen's guerilla war

The Karen are Burma's largest ethnic minority. Their fighters, trained by the British colonial army before the country gained independence in 1947, took up arms to force the newly independent Burmese regime to grant them broad autonomy in the states where they were in the majority. It was the main rebellion to have risen up in the 1950 against the military power in Rangoon, which was seeking to subjugate these tribes, which then represented almost half the country's population.

Neck X-rays : Diagnosis by Dr Pierre Nahum

Contrary to popular belief, necklaces do not lengthen the vertebrae of the neck, but they do put pressure on the ribs, giving the illusion of an elongated neck. According to Dr Pierre Nahum, a radiologist in Clichy (France): "There is no significant impairment of cervical statics or morphological changes. The spirals lower the lower cervical soft tissue and pull the upper cervical tissue upwards. The position induced by wearing the rings is unnatural and creates abnormal tension. The fact that two dorsal vertebrae are visible on the X-rays proves that the thoracic cage has been lowered, which may limit breathing capacity. When the rings are removed, it is difficult to keep the head upright, as the strapping induces muscular fragility through inaction. It therefore needs to be supported while the neck remuscles".

Text Brigitte Postel

Photos Catherine and Rémi Barbier unless otherwise stated

Article published in Natives magazine n°6 https://www.revue-natives.com/editions/natives-n06/

Read

Au pays des femmes girafesVitold de Golish, Editions Arthaud, 1958.

Burma - Visions of a lover of the Golden LandJérôme KotryEditions Transboréal, 2006.

The Zoo of the Giraffe Women: A Journey Among the Kayan of Northern Thailand, Martino Nicoletti, 2011. Kindle format.

Majestic BurmaFrançois Guenet, Frédérique Maupu-Flament, Yves Crapez, Editions Atlas, 2006.

NdebeleSergio CaminataActes Sud, 1998.

Children's book

Khin Kyi, giraffe-woman of Burma, Myriam Marquet, jeunesse L'Harmattan, 2015.

[1] Faced with the exactions of the Burmese dictatorship in reprisal against the Karen guerrillas.

[2] www.sideshowworld.com/81-SSPAlbumcover/Giraffe-Neck/Women.html

[3] The Salouen River rises on the Tibetan plateau, crosses into China in the mountainous north-west of Yunnan province, the Burmese Shan State and serves as the border between Burma and Thailand before flowing into the Gulf of Martaban (Andaman Sea).

[4] See François Guénet's report https://www.divergence-images.com/francois-guenet/portfolios/editorial-civilisations-gci-3013-1552.html

[5] United Nations High Commission for Refugees.

A magnificent, well-illustrated, comprehensive and highly instructive document!