In Japan, the tradition of tattooing is reserved for yakuza, the Japanese mafia. Still frowned upon by the population, tattoos are tolerated by Westerners and tourists, but remain negatively associated in Japan.

Generally speaking, tattooed people are frowned upon in Japan and are excluded from certain professions. This is even truer for women. Yet the ritual of tattooing dates back to the earliest Japanese civilisations. Clay statuettes decorated with tribal symbols have been found in tombs from the Jomon period (13,000 to 800 BC) (1). Among the Ainu, an aboriginal tribe of hunters, fishermen and gatherers living mainly on the northern island of Hokkaidô, cited since the 6th century, tattoos were a symbol of social belonging, spiritual protection or even ornament.

With the arrival of Buddhism in the 6th century, and also under Chinese influence, this traditional art form came to be regarded unfavourably.

Tattooing, from the Edo to the Meiji era

Tattooing flourished during the Edo period (1603 to 1868). A distinction was made between honour tattoos, which celebrated heroes, and prisoner tattoos. In the 17th century, tattooing was practised by the " bakuto " or professional gamblers, often linked to the world of crime, some of whose codes have been adopted by the yakusa, the Japanese mafia. They would tattoo a black circle around their arm for each crime they committed. Prisoners were also marked with symbols on their arms or foreheads until 1870.

Prostitutes also start practising irezumi for aesthetic purposes, which has the effect of accentuating the negative connotation of this custom. Kabuki literature and theatre would give graphic representations and figures to this tradition, which had become an art form. Kabuki literature and theatre gave figures and graphic representations to this tradition, which had become an art form: the heroes were fully tattooed warriors, and engravings and prints depicted dragons, tigers and koi carp, all symbols of Japanese mythology that were taken up by tattoo artists.

As Japan opened up to the world, the Meiji government (1868 to 1912), wanting to give a good image to Westerners, decided in 1872 to ban the practice of tattooing altogether. Tattoo artists operated discreetly, under cover of another activity. At the beginning of the 20th century, they found new customers: sailors on foreign ships. During the American occupation that followed the Second World War, the practice was legalised once again, but remained associated with the lower classes and organised crime.

Yakuza and tattoos

The practice of tattooing remains a trademark of the yakusa as well as the yubitsume (2), which sets them apart from the Japanese population. It's a way of imposing fear on those around them and, above all, an acknowledgement that they belong. In Japan yakuza are well established. It is the only criminal organisation in the world that has to declare itself as an association, and every one of its members has to register. However, modernity and police persecution have had a strong impact on the institution: from more than 200,000 members in the early 1960s, there are now fewer than 100,000.

Traditional tattooing using the tebori method

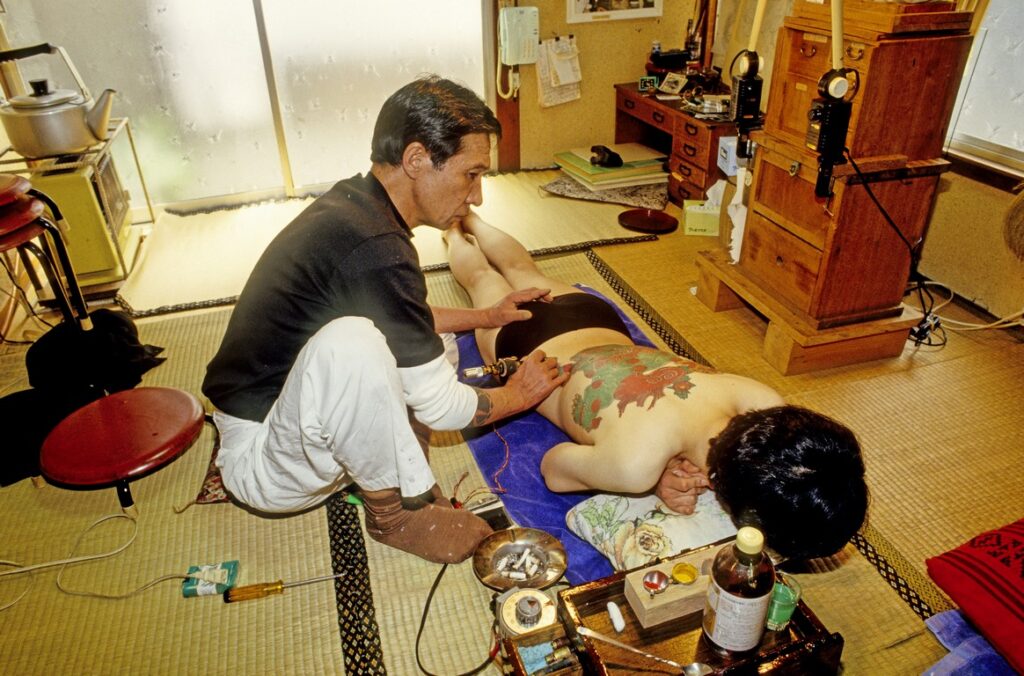

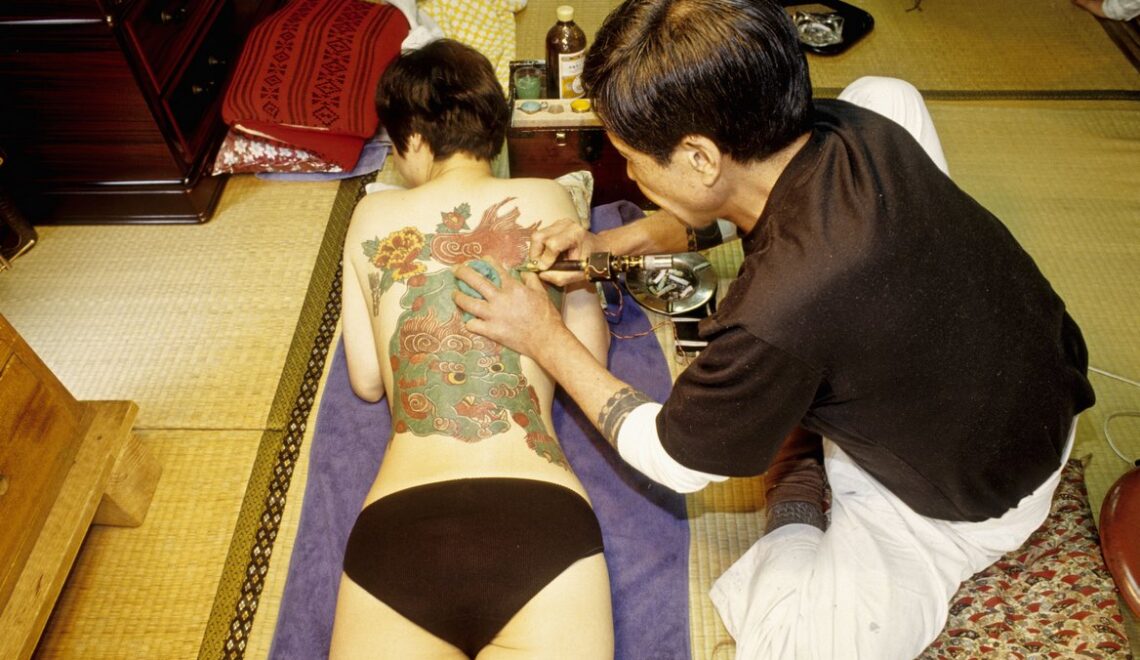

It is done on the ground, on tatami mats protected by a tarpaulin. This ancient form of tattooing, carried out using the tebori method, is more difficult for the tattooist than tattooing using an electric machine. The irezumi is instantly recognisable thanks to its distinctive patterns and bright colours.

Traditionally large in size, the tattoo generally covers the entire torso and can extend to the end of the arms and cover the legs. The ink is inserted under the skin using several needles attached to the end of a bamboo or steel stick. This ancient inking technique is still practised by a handful of master tattoo artists in Japan.

One of the main dyes used is Indian ink in sticks and also vermilion. The tattoo is done in colour on the shoulders, back and chest so that it can be hidden under clothing, and requires strength and courage.

Representations of dragons (magical creatures with great power) are very popular. The carp (koi) symbolises courage and power, the cherry blossom (sakura) fleeting beauty.

If you envy those beautiful old-fashioned tattoos, Mr Horitake, yakuza now wiser (he's missing a little finger!), will create a work of art on your epidermis in 25 4-hour sessions. It's a long and painful process: the metal needle pushes the ink under the skin. Mr Horitake uses the needle in the same way as in the past, but on an electrical device that he designed himself.

"The more beautiful the tattoo, the more intense the suffering. Tattooing and spiritual strength go hand in hand. Be careful, it can never be removed", explains the master tattooist. A tattoo can take several years to complete, and can cost the price of a very fine car - several tens of thousands of euros...

Some artists still draw as they did in the past. They find their inspiration in classical stories and mythology. Kneeling for the entire session, master tattoo artists have to concentrate hard to create these complex designs, which is why they cannot work for several hours at a time. Customers then have to come back or not.

1 - A few years ago, the TAV gallery in Tokyo exhibited a collaborative art project by tattoo artist Taku Oshima and photographer Ryoichi Keroppy Maeda, in which motifs from the Jomon period were inscribed on human bodies.

2 A yakusa who breaks the code of honour, makes a mistake or fails to obey an order, may practice the yubitsume. He offers his superior the last phalanx of his little finger as a sign of contrition or to make amends for an offence.

Text : Michèle Lasseur and Brigitte Postel

Photos : Sylvain Grandadam