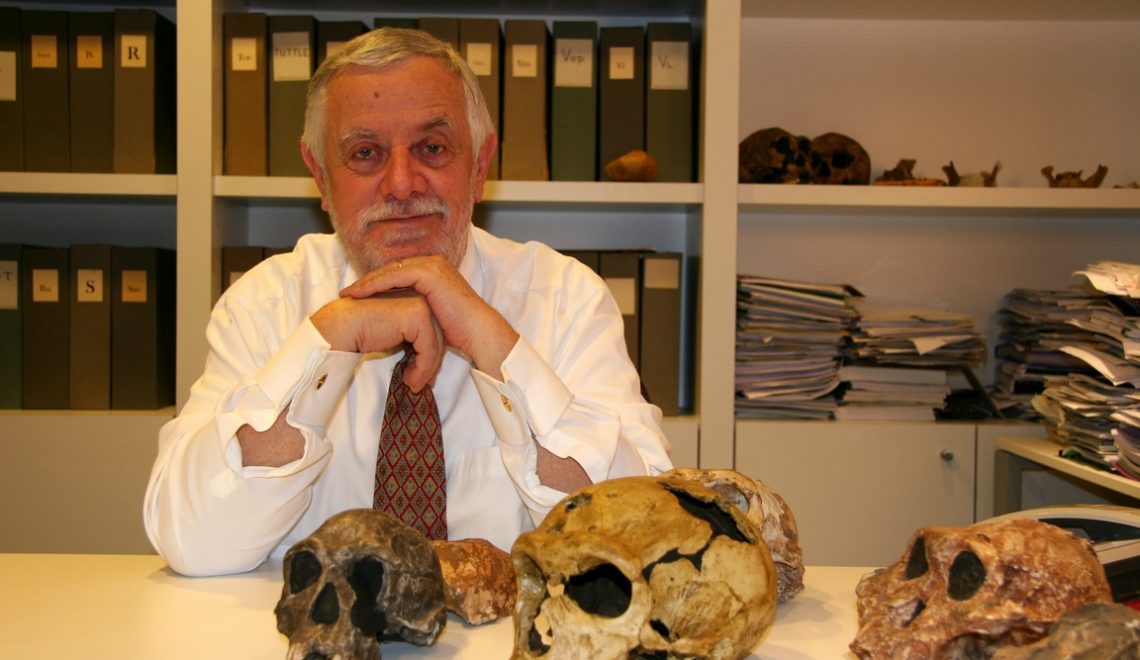

Palaeontologist and professor at the Collège de France, Yves Coppens died on 22 June 2022. Inextricably linked with Lucy, a 3.2 million-year-old australopithecus discovered in Ethiopia in 1974 during an international mission that he co-directed with the American Donald Johanson and the French geologist Maurice Taieb, Yves Coppens was a major figure in palaeontology. We met him in 2007.

What do we know today about man's origins?

The question of origins arises above all from the separation between the great apes and pre-humans around 10 million years ago.

Two lineages can be distinguished: paninae and homininae. The panininae lineage raises questions because it seems that there was a common ancestor to these two lineages. But we have no representative of the latter. Some authors wonder whether some panininae have been misidentified and wrongly classified as hominins. We do not have any pre-chimpanzees or panininae fossils. But it's true that sites - and fossils - in wet areas are less easy to excavate than in dry areas.

For a long time, pre-humans and humans lived side by side

As far as the hominin lineage is concerned, the work we have carried out shows a "bouquet" development, in other words a flowering of forms, with pre-humans living from 10 to 1 million years ago and then humans, from 3 million years ago to the present day. There was a fairly long period during which pre-humans and humans lived side by side. Some of these hominins could be more or less acceptable ancestors of humans: Australopithecus anamensis or Kenyanthropus, or even Australopithecus bahrelghazali familiarly known as Abel. But many uncertainties remain.

What we know for sure, however, and what I have been asserting since 1975, timidly at first and forcefully and vigorously now, is that man was born of climate change.

The (H)Omo event

As it was in the Omo valley, in southern Ethiopia, that I first brought to light in 1975 the link between the birth of man and the three-million-year dry spell, I called it a bad pun: the (H)Omo event. I can claim this because I worked for 10 years in East Africa, in geological layers that revealed to me that this major change in climate (from wet to dry) affected a hundred different species. These species all changed at the same time, adapting to life in a drier environment and adopting a diet rich in grasses and less based on leaves. It was at this point that prehumans, who used to walk and climb, began to walk alone. Their brains grew impressively in size. And it becomes omnivorous. This is nothing less than the appearance of the genus Homo, i.e. of man (charged only with his biological definition).

Then, from its tropical and African cradle, this man was to spread very quickly to other continents.

According to the Darwinian idea, certain individuals undergo genetic mutations and this new species takes over. Do humans adapt at all costs? And can we become extinct like other species have?

Of course it can disappear; it has happened to other species. But the history of its evolution shows us that it has adapted. All living beings adapt. Insects with leaf-shaped wings, for example, are just one of the many examples of life's extraordinary capacity to adapt. During the ten years I worked in Ethiopia, I saw around one hundred species transform in the right direction, in the direction that was best for their survival, in other words, their adaptation to a drying environment. And it is for this reason that I have sometimes challenged geneticists who claim that mutations occur randomly, because my experience contradicts them.

The 50 tonnes of bones I collected in Ethiopia show that all animals evolve in the right direction in terms of adaptability. I then assumed that there were genes capable of receiving information from the environment, and therefore from climate change, and capable of transmitting this information and transforming the offspring in the appropriate direction when the need arose. But it was too naive to be true. Biochemist Christian de Duwe, who won the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 1974, came up against the same problem: mutations were indeed due to chance (which is corroborated by genetics), but they were conserved and used appropriately by living organisms. It should be noted that this adaptability is valid as long as man is part of the ecosystem. At that point, three million years ago, man had no choice but to undergo climate change.

But with the advent of the tool, man's situation changed. He would also become cultural instead of merely natural. And little by little, his status was to be transformed in favour of a man who would no longer be subjected to nature but would try to conquer it. Thus, at the beginning of the Neolithic period, twelve thousand years ago, the last ice age came to an end, causing the waters to rise and a temperate climate to take hold. Grasses grew better and better, and people stopped to pick them. It was in the Near East that he did so. There, they became sedentary and invented agriculture and animal husbandry. This was the beginning of the production economy.

This is an example of climate change that man has perfectly mastered. Physically, it doesn't change, it stays the same Homo sapiens. The preponderance of the acquired over the innate is then very visible. But this shift from the acquired to the innate took place earlier. This is what I call the "reverse point", the moment when culture takes over, which I place at around 100,000 years ago.

How do you explain the slowdown in biological evolution?

Through the evolution of culture. Culture means knowledge, and knowledge means freedom and responsibility at the same time. The rise of culture has enabled us to liberate the body and find ways of countering environmental aggression, and this will continue to be the case until one day, perhaps, we won't be able to find any. For example, we see meteorites coming, but we don't yet have the ability to deflect them.

Unfortunately, we don't have long enough to find a cure for everything. There are currently emerging diseases for which we have no treatment. But we must have faith in science and in the genius of mankind, which may one day master plate tectonics, meteorite falls or viral attacks?

How do you see human evolution?

I see its evolution continuing, as it has developed from inert matter to living matter and from living matter to thinking matter. I can hope that thinking matter will prevail and that it will continue to exist.

Since our history over the last 15 billion years has been nothing but gradual, it seems to me that the same can be said of our future. We can hope that humanity will develop in the direction of a super-thinking or "better thinking" humanity. In any case, that we will reach a new level of understanding, leading to a more tolerant and ambitious humanity that will perhaps be able to predict certain geological or cosmic events, despite their random nature.

Today we have to come to terms with man's impact on nature, something that didn't exist in the past. How do you see the future?

Since the 19th century, the development of demographics and technology has meant that the conquest of the environment, which began three million years ago, has intensified to the point where we have gone very far, at the same time as we have become aware of the limits of our planet. Half of the Earth's landscapes are now man-made.

There is a certain amount of inertia at the moment when it comes to environmental issues, but I am optimistic that things will change.

Throughout the three million years of prehistory that I have studied, I have always seen humanity come out on top, because in the end it is its conscience that prevails. They have always been more responsible than they first seemed. But this awareness takes a little time, because in our society there is a lot of resistance to profits. But we have to be careful not to commit irreversible acts and stop playing the sorcerer's apprentice. But the fact that climate change has happened and is still happening is a given. And we need to be prepared to adapt to it. For the moment, since we have no control over natural conditions, let's content ourselves with controlling man-made conditions, i.e. the actions of human beings on their environment. That's already a pretty good programme.

Interview by Brigitte Postel

Photo: Brigitte Postel

This interview was published in Archeologia - n° 447 - September 2007