The Olmecs were the first of the great civilisations of Mesoamerica. Their name comes from "olmeca", which in the Nahuatl language means "the people of the land of rubber". (In the 16th century, "olman" referred to the Gulf coast, a region rich in tropical trees producing this material).

Today, most specialists agree that this culture played a decisive role in the development of the pre-Hispanic peoples. From the Zapotecs to the Aztecs, via the Mayas and Toltecs, all the civilisations of Middle America drew their roots from this source.

1,78 × 1,63 m.

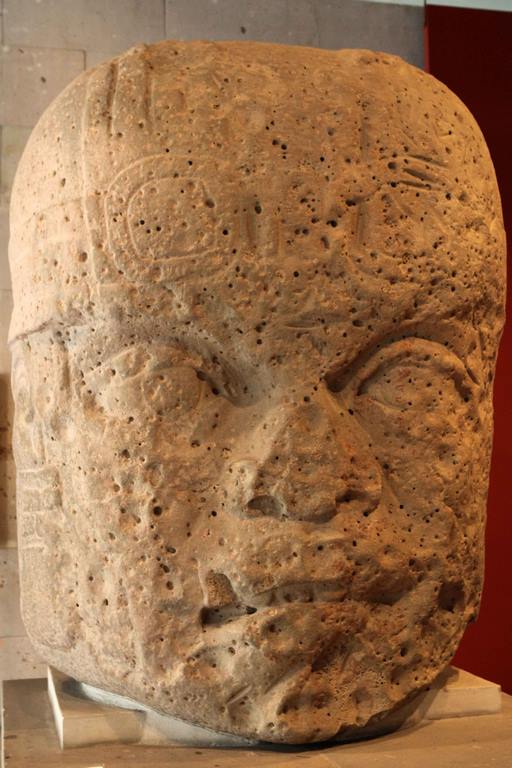

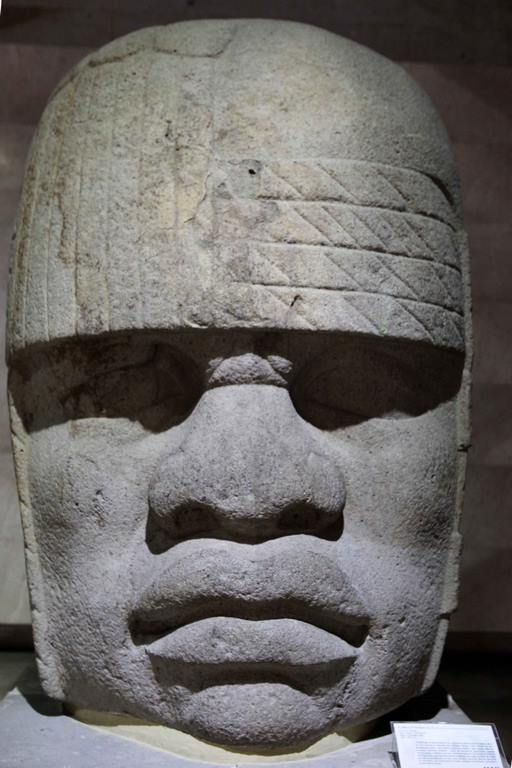

Head no. 4 is also carved from volcanic rock. The headdress (or helmet) is made up of four strings covered by a sort of cap with three tassels that fall down over the cheek. This would indicate the figure's hierarchical position. The back is also flat.

1200-900 BC. 1.78 × 1.17 m.

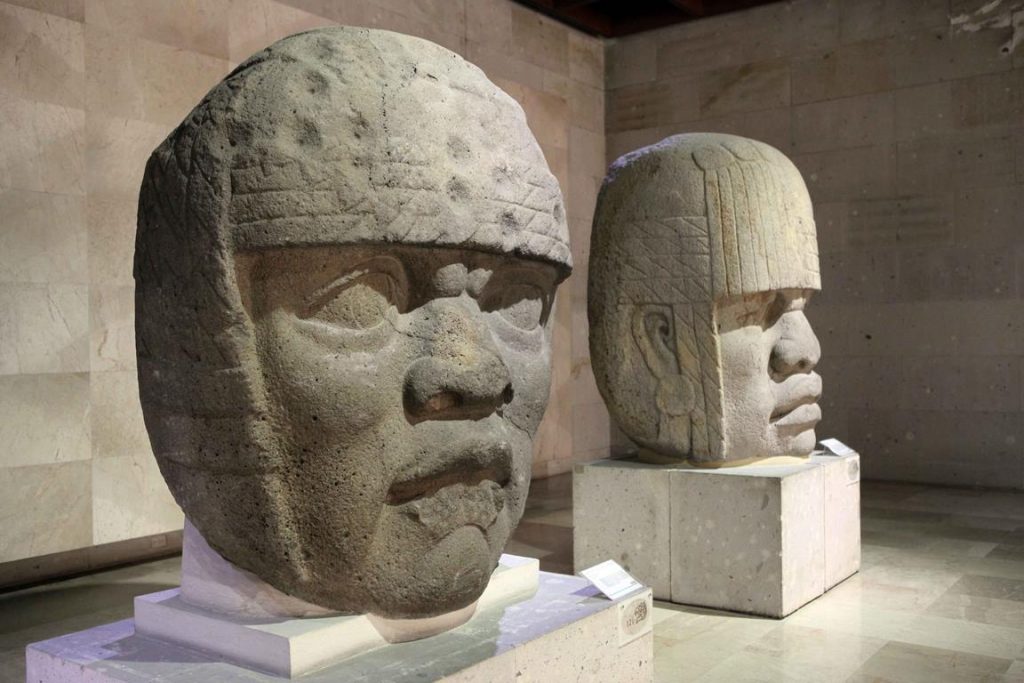

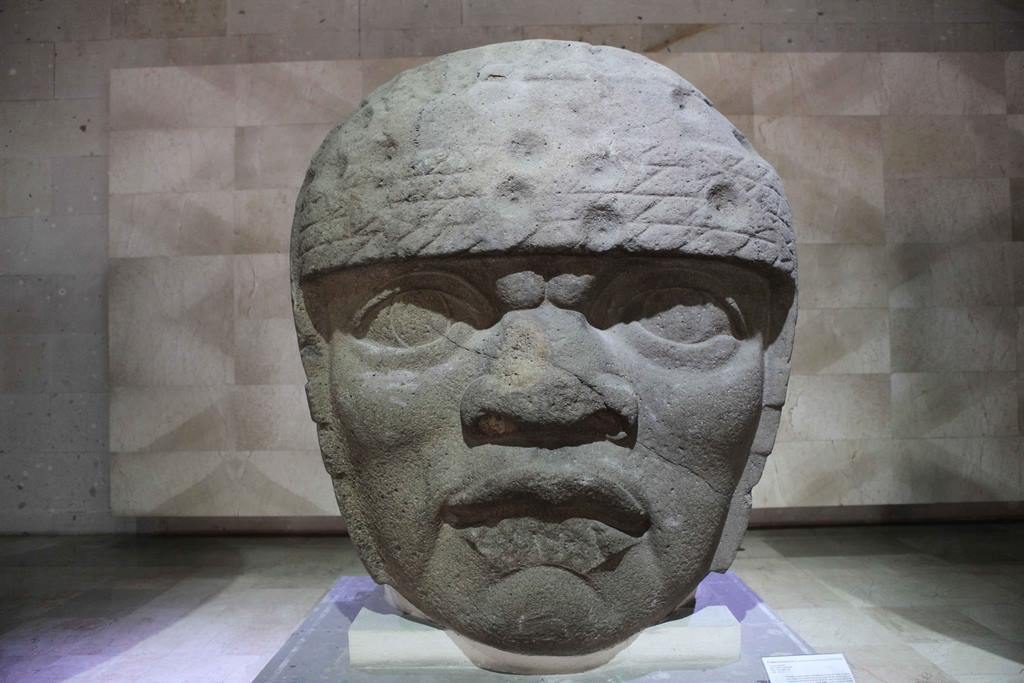

Between 1200 and 500 BC, almost a millennium before the Mayan cities, this heterogeneous population federated this immense territory. They built the first cities of Mesoamerica. It was in the Coatzacoalcos river basin, in southern Veracruz, that archaeologists unearthed cities, elite residences, ceremonial complexes and large-scale sculptures, including the famous colossal heads, all found in three of the great Olmec cities: San Lorenzo, Tres Zapotes and La Venta. A total of 17 heads, including 10 from San Lorenzo Tenochtitlan.

1200-900 BC. 2.85 m × 2.11 m.

The largest collection of monumental works

The Xalapa museum boasts the largest collection of monumental works (stelae, altars and 7 monumental heads) from this period of aesthetic apogee. Divided into six halls and three open spaces, the museum contains some 27,000 objects of Mesoamerican origin, displayed in a museography organised according to the geography of the state of Veracruz.

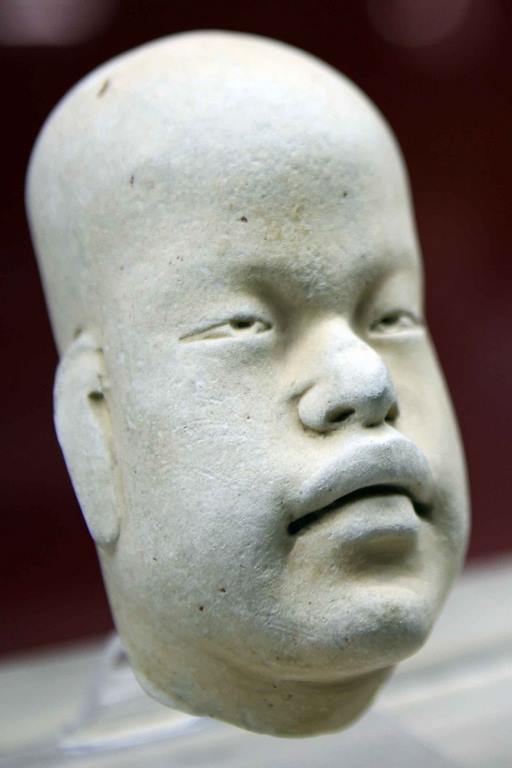

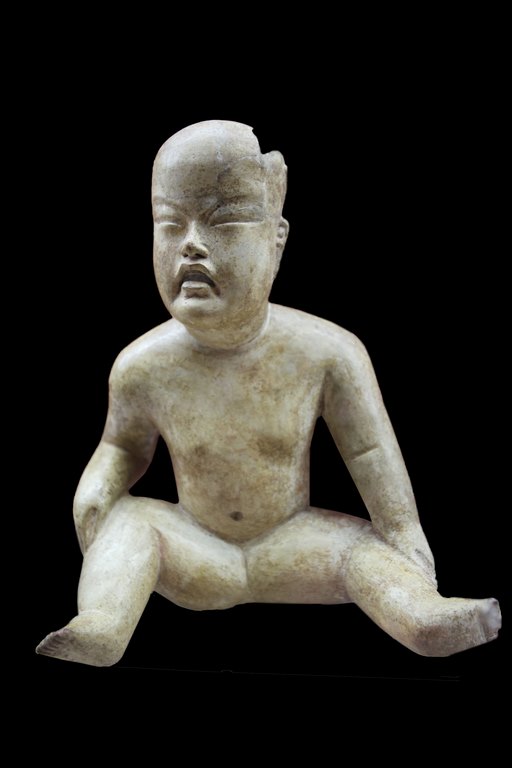

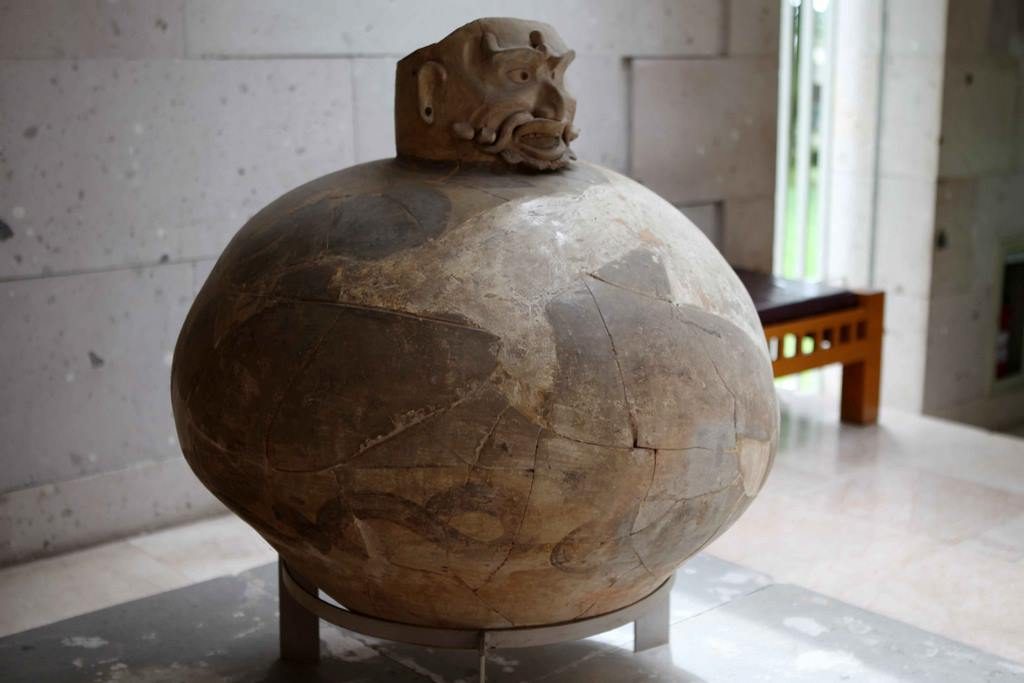

The mythical figure of the jaguar, whether anthropomorphised or not, is very common in Olmec statuary. The jaguar plays a key role in religious thought.

These heads, which measure between 1.47 m and 3.40 m and weigh between 6 and 50 tonnes, were magnificently sculpted from blocks of basalt from the volcanic area of Los Tuxtlas, several hundred kilometres from the ceremonial centres. How were these multi-ton blocks moved? They were transported by land over several kilometres using wooden logs, then loaded onto sturdy rafts that floated down the Papaloapan river to the sea, along the coast and finally up the Tonala or Coatzacoalcos rivers to reach the sites where the heads were carved using the direct carving technique.

According to art historians, the heads in the Xalapa museum are the best finished from both a formal and aesthetic point of view. The differences in the headdresses and the variety of features suggest that they are genuine portraits. The face is generally square. The jaws are wide and powerful. In addition to these physical constants, the artist never repeats himself, and instead offers a panoply of highly expressive male faces. Some are impassive and serious, others serene, and more rarely laughing, as in head no. 2 from La Venta. The heads undoubtedly represent dignitaries. Jacques Soustelle referred to "dynasts, priests or victorious athletes", while others think of ball players. However, it seems that the most plausible interpretation is that of a representation of the Olmec political and religious elite. For Caterina Magni, a lecturer at the University of Paris IV-Sorbonne and a professor of pre-Hispanic archaeology, "this statuary is part of the 'cult of the governor', which was to have a glorious posterity in Mesoamerica in a variety of forms".

A variety of artistic productions

In terms of iconography, the human figure is the main theme of Olmec art. This is followed by the hybrid figure, half human, half feline, and in third place, the animal theme. As well as monumental works in stone and small-scale objects in jade-jadeite, serpentine and obsidian, Olmec artists also excelled in working with clay and wood.

Anthropomorphic figures can also be seen (rather massive adults with shaven heads standing upright, ceramic sculptures).

Jade axes (petaloid or rectangular) and stone funerary masks are also among the most remarkable Olmec products.

In the artistic sphere, the Olmec heritage can be seen in the later cultures that continued to carve jade and cut large blocks of stone. "There are varying degrees of filiation. For example, while Tlaloc, the Mexican god of rain, clearly perpetuates the characteristics of the feline, Quetzalcoatl, the famous "Feathered Serpent", conceals them from the unfamiliar eye," points out Caterina Magni.

These fundamental traits bequeathed by Mexico's first great civilisation to later cultures have been present throughout the centuries. The cultural and historical continuity of Mesoamerica is, without doubt, exceptional. And the works in the Xalapa Museum bear witness to the development achieved by this little-known culture.

History of the colossal heads

The first colossal head was discovered by chance in 1862 (by a Mexican traveller by the name of José María Melgar y Serrano) at Hueyapan (now Tres Zapotes), in the south of the state of Veracruz, but at the time it was attributed to the Maya. It was completely excavated in 1938 by Matthew Stirling, the pioneer of Olmec field archaeology. This basalt head, about one and a half metres high and weighing around eight tonnes, is kept in the Tres Zapotes museum.

In 1925, more Olmec megaliths were unearthed during the travels of Frans Blom, a Danish archaeologist, and Olivier La Farge, a North American ethnographer. The two adventurers explored the Gulf Coast, then south-eastern Mexico, uncovering works of Olmec art and the site of La Venta (Tabasco). However, they attributed these remarkable remains to the Mayan culture, which fascinated the minds of the time. It wasn't until 1955 that archaeologists, thanks to the use of carbon-14 dating, challenged this theory and identified certain pieces as predating the Mayan civilisation. The last head, discovered in 1994 in San Lorenzo Tenochtitlan by a Mexican team led by Ann Cyphers, is very well preserved and of great plastic beauty. It can be seen in the small museum in Tenochtitlan.

https://www.uv.mx/max/

Text and Photos: Brigitte Postel