Located in the prestigious Renaissance Bourbon del Monte in Sansepolcro, Tuscany, the Aboca Museum tells the story of mankind's age-old relationship between man and plants, and the history of herbalism over the centuries.

Founded in 2002 by the Aboca laboratory, this museum is the brainchild of a visionary man, Valentino Mercati, who decided in 1978 to set up a laboratory focusing on the use of plants to treat his fellow human beings naturally. Convinced that lasting remedies for human ailments could be found in nature, he set up a 100 % organic production chain, from plant cultivation to marketing, including research & development and the production of food supplements. The result is a molecular and cellular biology laboratory with technological platforms that would make some European manufacturers pale in comparison.

The museum tour takes visitors on a journey that reintroduces medicinal plants to the art of healing through the ages. Drawing on past historical sources: herbariums, botanical and pharmacopoeia books, reconstructions of old pharmacies, etc., the museum?s designers have succeeded in conveying the art of apothecaries and pharmacists since the Middle Ages. Most of the objects in the museum come from the private collection of the Mercati family, while the rest were purposely purchased for the museum after it opened.

As soon as you enter, there are signs explaining the origins of the relationship between man and plants.

The mortar room

It houses a collection of mortars, the oldest of which date back to the 15th century. Apothecaries always had several of these, of all sizes, in bronze, alabaster, marble, iron, silver, hard stone, ivory, wood, etc. Their use dates back to the Neolithic period. Their use dates back to the Neolithic period. At that time, they were flat stones with a cup in the centre on which seeds were crushed. But mortar reached its apogee in sixteenth-century Italy, where it became a particularly elaborate objet d'art, covered in decorations of mascarons, mythological symbols and reproductions of plants or animals.

The History Room

The first traces of the use of medicinal plants date back to 2200 BC with the Sumerian Pharmacopoeia of Nippur, a collection of plants and remedies from the animal and mineral world, engraved on a clay tablet. This was followed by the Ebers Papyrus, written in Thebes in 1600 BC, and the Corpus Hippocraticum attributed to Hippocrates (460-356 BC), which lists 230 plants from the pharmacopoeia. Another example is the herbarium of Cratevas, physician to Mithridates VI (around 132-63 BC), of which all that remains of the text are the quotations from Dioscorides (practising in Rome in the 1st century AD) in his treatise De Materia Medica.

The advent of printing with movable type (around 1440) led to the publication of works devoted to plants, and more specifically herbariums, which were the first atlases of the plant world.

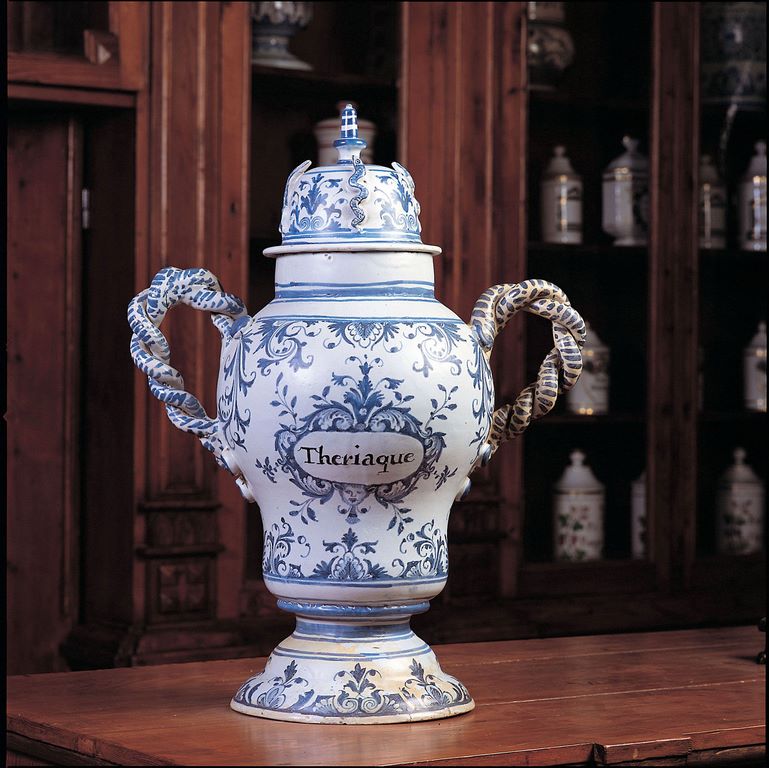

The ceramics room

For those who love ceramics, particularly majolica, this room contains a superb collection of medicine jars of all kinds.

After Hispano-Moorish earthenware, the result of the Islamic presence in Spain and Majorca (which gave its name to majolica), Italian high-fired ceramics began in Florence and Faenza (which gave its name to earthenware) in the 15th century. From the early 16th century, thanks to the presence of talented artists, it reached its apogee there, before developing in neighbouring towns in northern Italy: Forli, Ravenna, Pesaro and Siena.

The albarelle (albarelli) was the most common form of apothecary jar, used to store ointments and medicinal plants after drying. We can also see chevrettes (jars with handles and spouts), and ceremonial jars or apothecary?s theriac jars.

The decorative themes range from floral motifs on a white background to more elaborate figures such as portraits, grotesques and mythological or biblical characters. This type of decoration is known as a istoriatoThis means that it tells a story.

The glass room

An easy material to work with, glass has always lent itself to the production of containers (flasks, retorts, funnels, gourds, jars, beakers, blood-letting bowls, etc.) for the pharmaceutical industry. The oldest, small balsam jars, date back to the 2nd millennium BC and come from Egypt. With the advent of the blown glass technique in the 2nd century BC, the shapes multiplied according to the needs of users and the taste of manufacturers. Some bottles are engraved with acid, while others, dating from the 17th century, are decorated with hand-painted cartouches.

Plants and stills

For an apothecary in the 15th or 17th century, taking an interest in the three great sciences of the Middle Ages - mysticism, astrology and alchemy - was not a departure from rationality. In fact, Paracelsian-inspired "chemical philosophy" was an important current of thought, reflected in a number of works aimed at instructing apothecaries, among others.

The apothecary, which began in convents with the Jardins des simples, as well as in princely courts, is, according to Greek etymology, "an apothecary". apothékê "It was also a centre of empirical knowledge. It was also a centre of empirical knowledge, where the role of the apothecary, a great connoisseur of medicinal plants, was to prepare remedies to treat the sick.

An authentic 19th century pharmacy

After passing through the phytochemical laboratory, we come across the poison cell.

All the toxic and poisonous products that pharmacists may need for certain preparations are kept there.

This low door is a symbol of passage between the profane world and that of the initiated. Beyond the door, the places - in this case, the poisons room - are accessible only to those who have the knowledge and the humility to admit that knowledge comes from acknowledging that "we don't know. "

The walls are covered with wooden furniture to store the various drugs and plants, so that the three main functions of the dispensary can be carried out more rationally: storing the various products, preparing the medicines and receiving customers for dispensing. A central counter with a trebuchet is dedicated to the manufacture and retail sale of magistral and officinal preparations. The décor of the pharmacy is well thought-out. In addition to their practical value, the richly decorated chevrettes and albarelles reflect the social status of the pharmacist.

Explorers brought animals and plants back to Europe. By hanging crocodiles in their dispensaries, apothecaries wanted to show their exotic side.

The Bibliotheca Antiqua

Before leaving this astonishing and unique museum, we will have the privilege of visiting the library, where many researchers from all over the world come to work. It can only be visited on reservation for study purposes.

This highly protected cave, equipped with temperature and humidity sensors, houses some 2,500 books on plants, pharmacology, chemistry and medicine. These books date from different eras: incunabula from the early days of printing, herbariums from the 16th century, and more recent masterpieces. The www.abocamuseum.it website lists them, and some can be consulted online.

Text: Brigitte Postel

Photos: Brigitte Postel and DR

Aboca Museum

Palazzo Bourbon del Monte

Sansepolcro

http://www.abocamuseum.it