Like calligraphy and ikebana, sad? (the Way of Tea) is a traditional art, influenced by Taoism and Zen Buddhism, in which powdered green tea, or matcha, is prepared in a highly codified way by a tea master after many years of apprenticeship. Drinking a cup of tea follows a precise ritual and can be a source of intense spiritual communion, as well as an aesthetic experience in which painting, calligraphy, poetry, the art of ceramics and floral art (ikebana) all play their part.

Being a chajin - a practitioner of the Way of Tea - is not something you can improvise. It is a long, arduous and costly path, an art in which all the senses will develop over the course of the sessions, according to a rigorous and imposed etiquette, both for the tea master and for the guests. With years of practice, the tea ceremony teaches you to live in the present, in true communion with the tea master, the guests, the elements and nature. It allows you to develop an extraordinary state of alertness and attention, a full awareness of the moment. More than just a beverage, tea gives life to a school of poetry and beauty, and a discipline for the conduct of life.

A ritual inspired by Zen Buddhism

Tea was introduced to Japan from China in the 11th century, but the craze for this beverage began in earnest in the 12th century with the monk Eisai, who had studied the most recent currents of Buddhism, particularly Zen, and brought back tea seeds from the Middle Kingdom. This art of drinking tea first developed in monasteries and was inspired by the Zen monks? ritual of drinking tea one after the other from a bowl in front of the Bodhi Dharma statue. Before spreading to the nobility who frequented these places, and then to the samurai caste, who had no access to the other prerogatives of the aristocracy. But their libations (chakai) were exuberant, a far cry from the ceremony and ritual instituted in the 15th century by the master Murata Shuk? as a reaction to these licentious banquets. This master laid the foundations for a more sober and uncluttered Way of Tea, the Wabi-ChaIt sets out the four values that should enable awareness of the moment and self-transformation: harmony, respect, purity of body and mind, and tranquillity.

Wabi-sabi: simplicity and the art of imperfection

This tea, "Japan ennobled it and turned it into an aesthetic religion, Theism".writes Okakura Kakuzo in The Tea Book. But it wasn't until the 16th century that the great tea master Sen Sôeki or Sen no Rikyû, more commonly known as Rikyû, established this enduring tradition. At the age of 17, he studied tea under Kitamuki Dochin while following Zen training at Daitoku-ji temple. It was from the ritual instituted by the Zen monks of successively drinking tea from a bowl in front of the Bodhi Dharma statue that the sad? ceremonial was born. As a purist, Rikyû established the spiritual principle now known as wabi-sabi: simplicity and the art of imperfection. Following his death by hara-kiri, after a final tea ceremony to which he had invited his friends, three schools of tea, all run by his descendants, came into being: omotesenke, urasenke and mushakojisenke, the urasenke school being the most widespread in Japan today.

The Tea Book was written in English in 1906 by Okakura Kakuz? (1862-1913) to convey to Westerners the very atmosphere and spirit of the tea ceremony (chanoy?) and the way of tea (sad? or chad?).

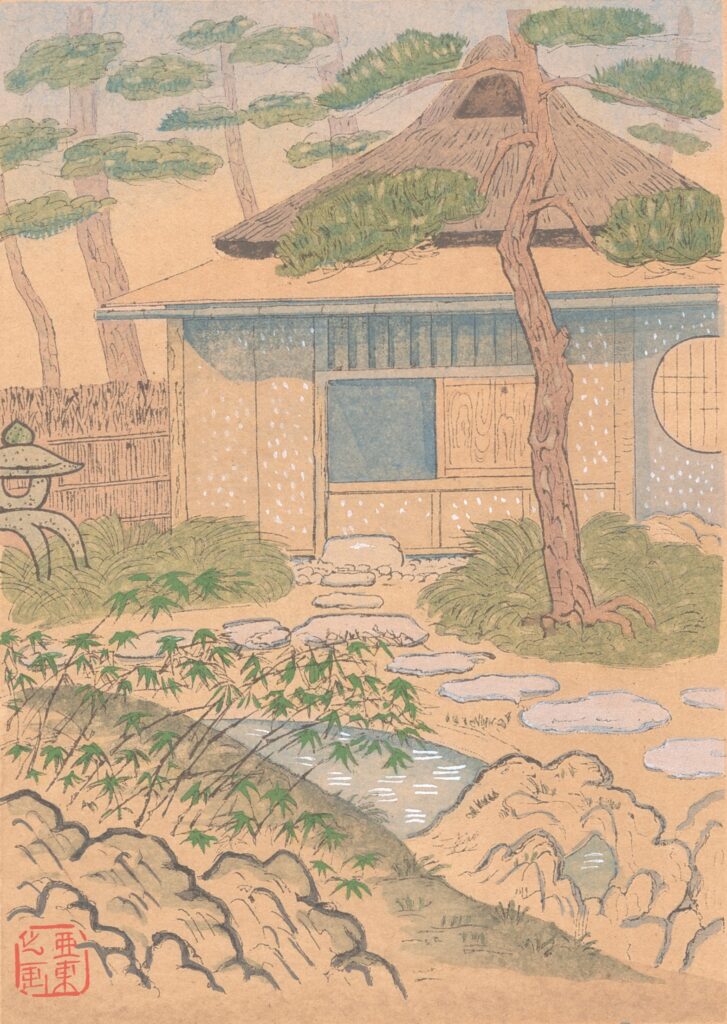

In 1930, Bibliophiles du Faubourg published Le Livre du thé in an admirable edition featuring a translation by art critic and poet Gabriel Mourey (1865-1943), a preface by Thomas Raucat and watercolours by J. A. Tohno.

This book, published by Citadelles & Mazenod, is a facsimile of the original limited edition of 110 copies. It is bound in Japanese style in an illustrated hardback slipcase. Illustrated full-paper lined cover 152 pages, 9 watercolours in-text by J. A. Tohno and 8 out-of-text illustrations, some gilded Format: 19.5 x 25.6 cm. Publication date: 12 April 2023. Price: 49 ?

The author

Okakura Kakuz? (1862-1913), a Japanese scholar and son of a high-ranking samurai, was one of the leading figures in Japanese art and culture. He contributed to the preservation and development of Japanese art, notably by helping to create the great National Museum (at the time the Imperial Museum) in Tokyo and the Nihon Bijutsuin ("Art Institute of Japan", 1898). In 1910, he became curator of Asian art at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. He wrote The Ideals of the East (The Ideals of the Orient, 1903) and The Awakening of Japan (The Awakening of Japan, 1904), in which he set out the traditional values of the East, which were then little known in the West.