Crete is not just an island: it's a world. A mountain in the middle of the Aegean Sea, a crossroads of civilisations, a stage where every stone whispers a story.

Ancient Crete and contemporary Crete are the stuff of dreams. The seaside resorts attract tourists from all over the world, while the hilltop villages continue to vibrate to the rhythm of religious festivals and local markets. Busy beaches give way to deserted coves, but olive groves and mountain vegetable gardens retain their ancestral rhythm. Here, antiquity meets the modern world.

It all begins with Minos, the palaces of Knossos and Malia, and the colourful frescoes featuring dancing acrobats and bulls. The first European civilisation, Minoan Crete has left indelible traces: pot-bellied jars, red columns, tablets engraved with mysterious signs. These vestiges still speak to the 21st century like a promise of impetus and beauty.

Then came the Romans, who turned Crete into a granary; then the Byzantines, who planted monasteries and icons; the Venetians, who built ramparts and palaces in the towns; and finally the Ottomans, whose mosques and hammams still bear witness to their long presence. The island resisted each conquest, thanks to its mountains, an inviolate refuge where language and customs remained. Crete was also a land of incessant uprisings, until the twentieth century, when it became a symbol of resistance against the German occupiers.

Heraklion: in the footsteps of Minos

Under the sign of Hercules, ancient Candia is Crete's largest city and the island's capital. You can wander between Venetian fortifications, Ottoman domes and rows of shops selling cheap souvenirs and traditional olive oil.

I start by walking along the Venetian walls. Massive and stubborn, they give the city its bastion profile. At the far end, the fort of Koules still watches over the entrance to the port, like an old lion that has not forgotten the bite of battle. The ferries from Athens dock here, pouring in tourists in shorts, where the galleys of the Serenissima once docked. On the quayside, fishermen repair their nets, unperturbed.

From there, I walk up towards the central market. The smells change with every step: olive oil, smoked cheese, dried thyme. The shopkeepers greet me in Greek, sometimes in English, often in the broken French I learnt as a child. They hand me figs still warm from the sun and a glass of discreet raki.

The walk then leads to the Piazza dei Lions, the beating heart of the city, where the Morosini Fountain takes pride of place. Inaugurated in 1628 by the Venetian governor Francesco Morosini, it is known as the "Lion Fountain". Children play, students linger and tourists photograph.

Further on, the church of Saint Titus tells a different story: that of the Byzantines, then the Turks, then the returning Greeks. In these stones, dominations are superimposed, like badly erased tracings. In front of the iconostasis, a woman lights a candle, indifferent to the visitors. Faith here is an everyday, almost domestic gesture.

The archaeological museum

As a memorial to Greece, the museum houses one of the richest Bronze Age collections in the Mediterranean. Visiting the museum is not just about contemplating objects: it's about reconstructing a civilisation, the Minoan civilisation, which flourished on Crete between the 3rd and 2nd millennia BC.

From the very first rooms, the frescoes of Knossos are the oldest evidence of painting in Greece. They are unique in the Aegean world for their intact polychromy, for the movement that animates them, and for the way in which they depict man and nature without warlike emphasis.

The famous "Parisienne", as it was nicknamed by archaeologists in the early 20th century, bears witness to a pronounced taste for finery and the elegant representation of women. These images are not mere ornaments: they reflect a world where appearance and gesture counted for more than heroic narrative.

The bull: sacred animal and divine mediator

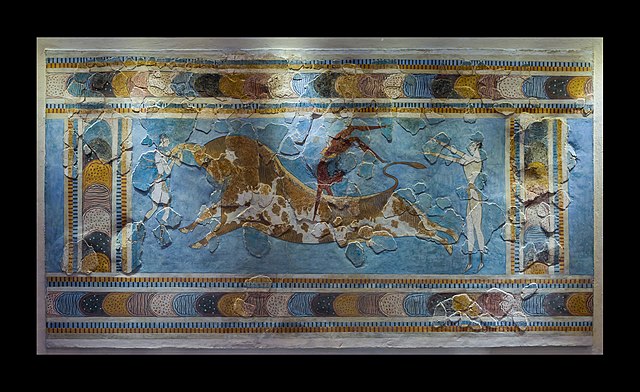

This original 'Taurokathapsia' fresco comes from Knossos palace. It shows a bull charging towards the left. Three figures surround it, performing all the phases of a somersault. On the left, a woman is preparing to jump by grasping the animal's horns, while a man is jumping upside down over the bull's back and, on the right, another woman, with her arms raised, has just landed. Around 1800-1700 BC © Jebulon/Commons.

Another important set of scenes are those of bullfighting. On the fresco of the "Taurokathapsia" (jumping over the bull), the practice of the acrobatic somersault lends credence to the idea of a sporting feat comparable to the Greek Games. But it may also have been a ritual practice. The bull was a sacred animal throughout the eastern Mediterranean, and in Crete in particular: leaping over it was perhaps a way of showing man's mastery over animal power, without destroying it. The image expresses less a feat than the harmony sought between the two.

The rooms reveal an essential characteristic of Minoan Crete: the almost total absence of war iconography. Whereas the Mycenaeans, their mainland contemporaries, celebrated combat and the hierarchy of chiefs, the Minoans favoured dance, festivals and contact with the sea and nature. This crucial difference suggests a differently organised society, where power was expressed less through violence than through ritual and the redistribution of wealth.

The museum displays small objects, often more enigmatic than the frescoes: the figurines of goddesses with snakes, found at Knossos, are among the pieces that have been puzzling visitors for over a century. These topless earthenware "goddesses" were found in the Treasury rooms in 1903. Were they fertility goddesses or ritual figurines used in domestic or palatial settings?

Goddess with snakes. Heraklion Archaeological Museum. © Rigorius/Commons.

The Heraklion Archaeological Museum does not just show isolated masterpieces. It restores the coherence of a culture which, before the invention of the city and the Olympian gods, invented another language: that of colours, movement and celebration.

Minoan jars: forms and uses

In the rooms of Heraklion's archaeological museum, you'll notice the imposing presence of the great pithoi (1), the massive jars that lined the palace storerooms. Sometimes over a metre and a half high, decorated with raised bands or marine motifs, they were used primarily as storage containers. The Minoans used them to store oil, wine and cereals: the foodstuffs needed for the palace economy, which was based on collection and redistribution. These jars are more than just containers: they embody the palace's role as a management centre.

Larnax: a funerary container

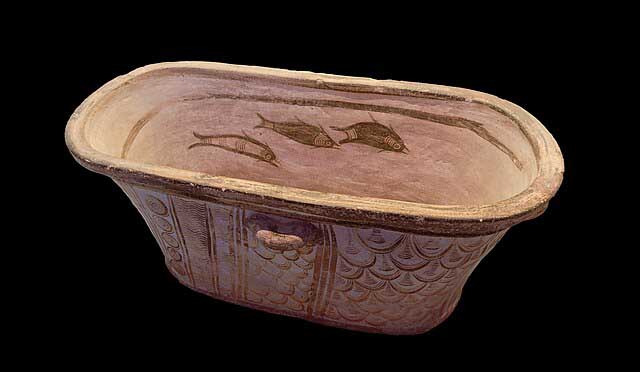

Among the utilitarian jars and vases on display at the Heraklion Museum, there are some surprisingly funerary shapes: larnax. These are terracotta chests, sometimes simple rectangular boxes, shaped like small, squat bathtubs with double-sloped lids.

They have been found in Cretan necropolises since the 14th century BC. The deceased was laid in a folded position, as if returning to the earth's womb. The small size of these coffins explains this posture: the clay imposed its limits, and the body had to bend to them.

Larnax with dolphins. Heraklion Archaeological Museum. © Jebulon/Commons.

Visitors will be amazed by the painted decorations. The walls of the larnax are covered with motifs that belong to the religious and symbolic repertoire of the period: spirals, rosettes, marine animals, as well as ritual scenes featuring offerings, funeral carts and altars. Death, in this context, is not represented as a brutal rupture, but as a continuity of the living world: the same sea, the same flowers, the same gestures accompany the passage. More than grandiose monuments, these modest, decorated coffins express the Cretan vision of death: a stage integrated into the cycle of nature, a permanence of forms and colours beyond the disappearance of beings.

Knossos: at the heart of Minoan civilisation

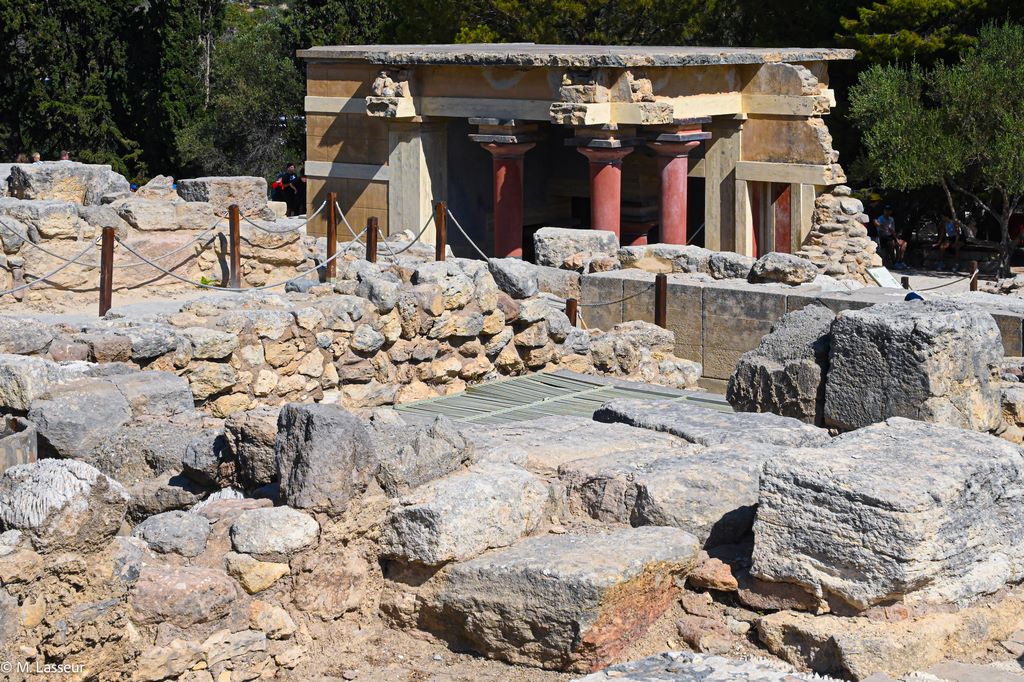

Knossos offers a different kind of Crete: one of legends and frescoes. This Cretan archaeological site, located 5 km south-east of Heraklion, is inextricably linked to that of the British archaeologist Arthur Evans. In 1900, he began excavations and discovered the Minoan civilisation (named after the King Minos).

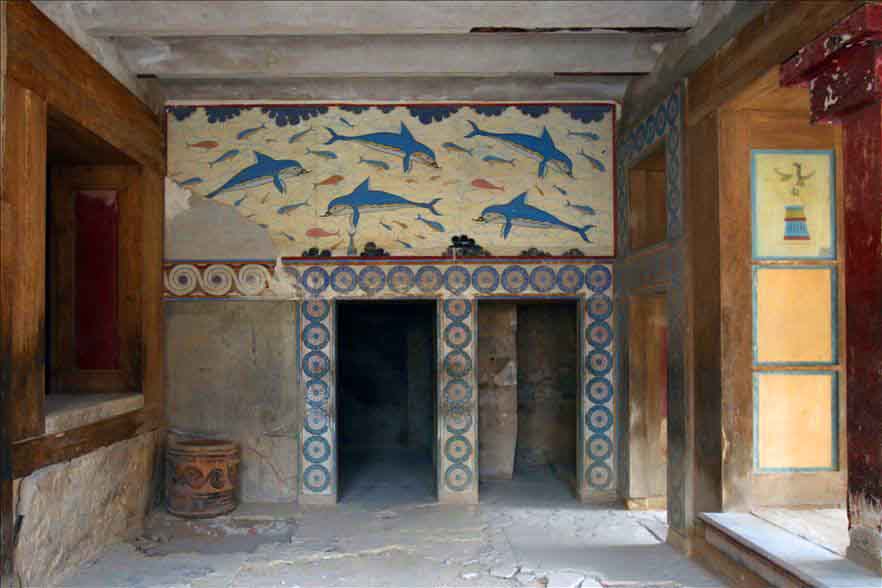

As in fairy tales, the guides repeat "Minos, Ariadne, Minotaur..." but you only have to cross the first carmine-red staircase to feel something else: the trace of a civilisation that, 4000 years earlier, had the luxury of painting dolphins on the walls.

Arthur Evans has reconstructed a great deal, sometimes too much; nevertheless, the scarlet columns and the frescoes of young acrobats facing the bull give the impression of a world that is both distant and familiar.

In the central courtyard, a breeze rustles through the air; it's almost as if you can hear the locked Minotaur panting or the echo of an ancient choir. Imagine... In Crete, under the sun that warms the blond stones, tourists walk on ground trodden more than 3,500 years ago. Knossos, now known as the "palace", was much more than just a residence: it was a palatial city, a world in miniature.

A few steps and we're in a huge courtyard. Perhaps this is where these strange games took place, with young men and women leaping over the bulls. Sport or ritual? Nobody really knows. But the bull is at the heart of all Cretan legends: the Minotaur, the Labyrinth, theAriadne thread... Almost everything was born here.

Let's move on. Here are corridors that turn, rooms that link together. It's easy to see why the Greeks later called it a "labyrinth". Was it really that complicated? Probably not. But the more you lose yourself in this succession of rooms, the more you understand that memory has embroidered this myth.

And there, on the walls, a few fragments of colour. Blue dolphins are still leaping up a wall. These paintings are more than frescoes: they are moments in life. The dolphins in the palace, painted in a room probably reserved for a queen, evoke a familiar relationship with the sea. Women with eyes highlighted in black, young men with bare torsos, the sea everywhere, omnipresent.

Then came the storerooms, vast corridors lined with huge jars known as pithoi. Here, oil, wine and cereals were kept: everything that fertile Crete produced. Here, the palace became a granary, a safe, an economic centre. Therein lay the secret of Knossos: a society that centralised wealth, redistributed it and organised it. A kingdom with no known army, but a meticulous administration.

And everywhere, mystery. Who really ruled Knossos? Was it the semi-legendary King Minos, or a succession of prince-priests? What role did the topless women found in statuettes play, brandishing snakes like sceptres? Was this a society in which the sacred was achieved through feminine grace? We don't know. But these statuettes of topless women brandishing snakes tell us at least one thing: here, the power of the sacred had the face of the feminine.

At Knossos, you walk between two worlds: the concrete world of stones, staircases and red and black columns; and the invisible world of the myths that the Greeks have woven around these ruins. This is undoubtedly why Knossos is so fascinating: because visitors are both on an archaeological site and in a legendary setting. And you can still hear the footsteps of the Minotaur echoing through the corridors.

Here we are in the large central courtyard. You can imagine it full of people on the day of a festival: musicians, priestesses, young men preparing to leap over a bull. Yes, it was here that this strange bullfight took place. The bull charges, and the athlete grabs his horns, leans on them, leaps up and falls back behind the animal. Was it a game? A ritual? Only the Minoans knew. For the visitor, it's an enigma.

Now let's look at the corridors. They turn, intersect and lead into narrow rooms. You get lost. Here, Theseus searched for the Minotaur, helped by the Ariadne thread. The monster never existed, of course. But the footsteps of a modern visitor echo so loudly through these corridors that you can still hear his breath.

Knossos is a crossroads where archaeology and legend meet. Here, in the ruins, the tourist is the heir to a dream. For three millennia, between the red columns and blue frescoes, people have been searching for the door to the Labyrinth.

Rethymnon: a Venetian jewel

The name Rethymnon may sound like a gentle invitation to stroll, but behind every stone, every alleyway, there are centuries of tension, trade and survival. Arriving via the Venetian port, you are struck by the mixture of deceptive calm and ancient power.

The quays were built in the 16th century to protect the town and enable ships to load and unload goods, but also to keep an eye on the pirates and Turks lurking offshore. At the time, the inhabitants lived under a constant threat between the need to trade and the fear of invasion.

Rethymnon's main attraction is the Fortezza, a huge 16th-century Venetian fortress that dominates the town. It is also an observatory of history. Imagine the Venetian soldiers on these walls, scanning the horizon, counting enemy sails, sending signals, knowing that the city's survival depended on every decision, every hour of vigilance.

If you go deeper into the old town, you discover a patchwork of cultures. The Venetians left their architecture behind, the Ottomans transformed some buildings into mosques, and yet within these walls, in these time-worn stones, you can feel the stories of the inhabitants, anonymous but resilient. The Rimondi fountain is a perfect example: it's not just decorative, it was used every day by the inhabitants to drink, wash and survive.

And then there's the sea. Always present. Always threatening and welcoming at the same time. It has brought wealth and goods, but also wars and epidemics. Every wave seems to whisper tales of sailors, merchants and privateers. It's easy to see that Rethymnon is not just a place on a map: it's a crossroads where people and events have intersected, sometimes brutally, often silently.

Margarites: the village of potters

Nestling in the heart of olive groves in the mountains, around 30 km from Rethymnon, Margarites is a small traditional village of 350 inhabitants, considered to be one of the traditional centres of pottery in Crete. There are more than 16 pottery workshops, each with its own unique style, combining modern and traditional techniques.

Mariniki Mania and Giogis Dalamvelas, craftsmen and artists, shape clay with a gesture that combines memory and invention. Each object they create - salt shakers, whistles, watering cans, jars, jugs - tells a different story of Crete: through everyday life, play, work and celebration.

The salt shaker is a companion at mealtimes, a silent presence at the centre of the table, recalling the rites of sharing and hospitality. The whistle, a musical and playful miniature, recalls spring festivities and children's games, carrying the memory of sound and shared joy.

The sturdy, pot-bellied watering can embodies the vital link between the human hand, water and soil, a symbol of patience and agricultural continuity.

Jars and jugs carry on the Minoan tradition of storing oil, wine and water, and playing a symbolic role in weddings and domestic rites.

Tourism and modernity notwithstanding, the island's customs and traditions endure: pottery, dance, song and farming. The Cretans are acutely aware that they are the inheritors of a rebellious and fertile island, where memory and beauty mingle at every street corner, in every daily gesture.

Accommodation

Kappa Club Iberostar Creta Marine 5*

www.kappaclub.fr

See our report on the hotel https://universvoyage.com/hotel-iberostar-kappa-club-creta-marine-5/

Read more :

An island of contrasting landscapes, from high plains to coastline; the history of this land, cradle of founding myths, marked by Venetian and Ottoman conquests; its architecture, from Minoan palaces to Byzantine monasteries.

There are 14 itineraries for exploring Crete, from the archaeological treasures of the Heraklion Museum to the labyrinth of Knossos, from the ports and fortresses of Chania and Rethymnon to the monasteries of Arkadi and Toplou, with close-ups, appendices, paintings by painters and writers and a map. As well as keys to understanding: history, arts and traditions, architecture. A vade mecum.

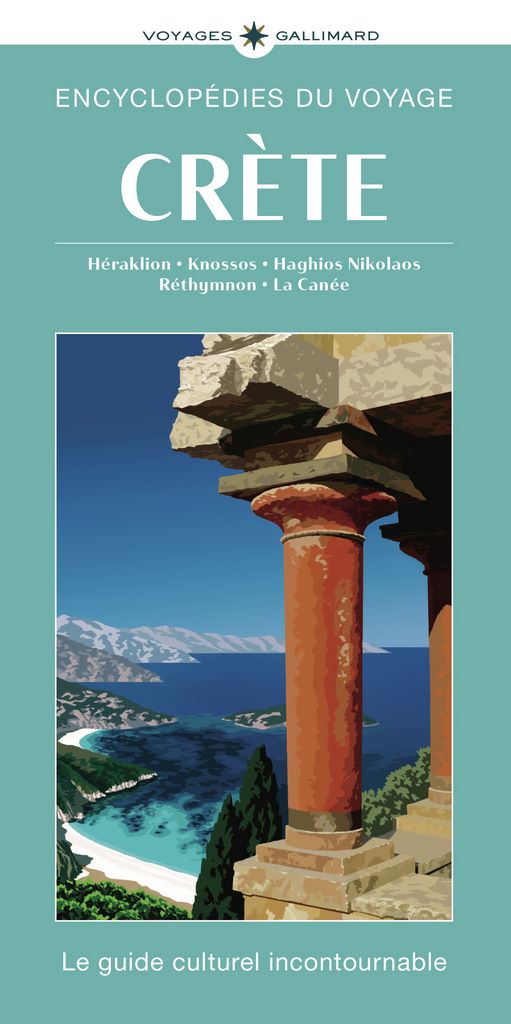

CRÈTE, Travel Encyclopaedias

Editions Gallimard Loisirs The Essential Cultural Guide 2025, 322 p., €27.50

@voyagesgallimard

1- A pithos (πίθος) (plural pithoi) is a type of large ancient Greek pottery, a deep jar with a more or less narrow base.

Crete Tourist Office

https://www.incrediblecrete.gr/fr/

Text : Michèle Lasseur

Photo opening : The Venetian port of Heraklion guarded by the fortress of Koules. In the background, Mount Stroumboulas. © C. Messier/Commons.