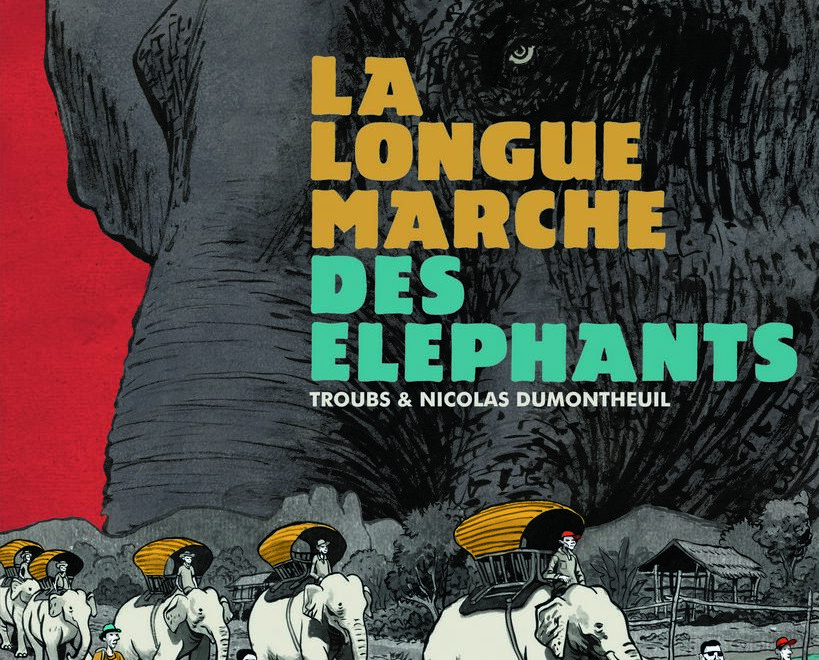

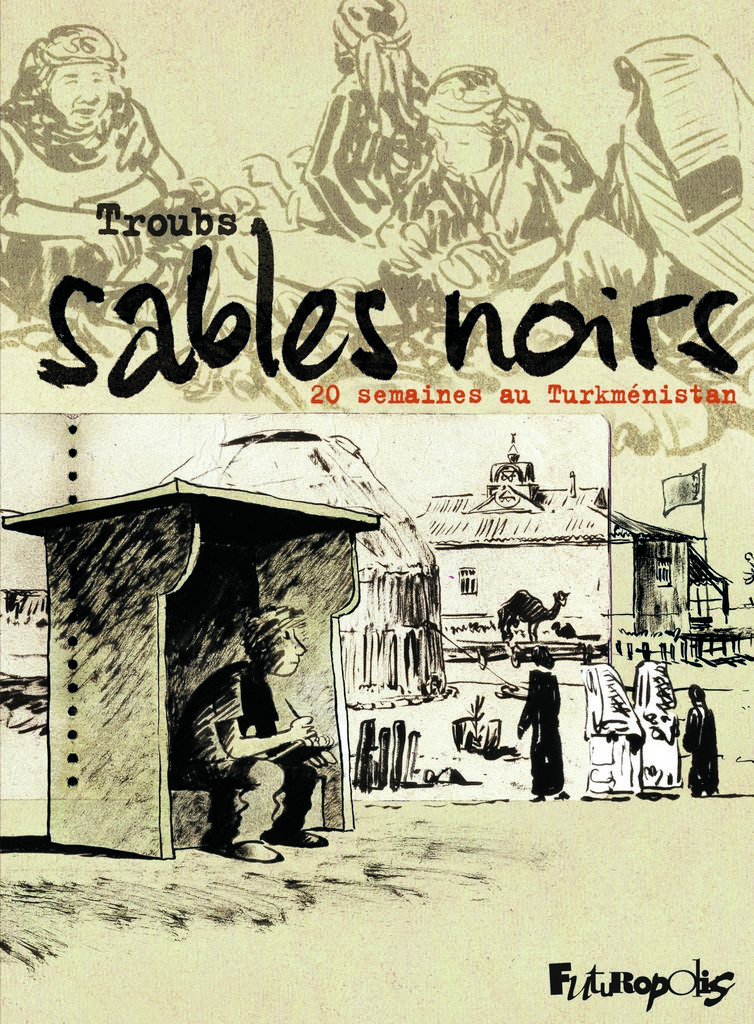

Troubs is, as he likes to call himself, a «travelling artist». A lover of nature, he travels to little-known places as a keen observer of the worlds he criss-crosses and the lives he shares. From Laos to Turkmenistan, Nunavut to Indonesia, Troubs often concludes his experiences with a documentary comic strip. Since the late 1990s, he has explored themes relating to indigenous peoples, ecology, memory and cultural transmission.

Table of Contents

Troubs' work is not confined to telling stories: it seeks above all to make visible communities that are often marginalised, while questioning our relationship with nature. Troubs highlights the fragile beauty of the cultures he encounters, the everyday gestures, the changing landscapes, but also the anxieties that run through societies. His simple, warm style, often accompanied by sensitive text, captures the intimacy of encounters and the depth of exchanges. His notebooks become bridges between distant realities and our own imaginations, inviting us to reflect on what it means to inhabit the Earth together.

How did you come to meet and work with indigenous peoples?

Initially, it was simply a desire to travel. In 1999, I went alone to Madagascar, on a simple tourist visa, to stay for three months in fairly «roots» conditions. My intention was to draw, to meet people and to recount my experiences in the form of autobiographical comic stories. During my three stays in Madagascar, I discovered different ethnic groups, which led to my first album, Manao Sary - Madagascar logbook (2001).

Then I went to Australia, to join an Australian friend living near Perth. I stayed there three times, always for long periods, and it was there that I made my first contacts with the communities. aborigines. They opened their doors to me and shared their intimate relationship with the land, an experience that has had a profound effect on the way I see and describe the world. Living in the Dordogne countryside, I've always been attracted to the rural side of things. Wherever I go, I always favour rurality.

What is it about these cultures that particularly appeals to you and makes you want to depict them in comics?

I wanted to highlight cultures that are rarely mentioned in the media, to give them visibility, and to show through drawings that there are ways of life that are different from our own, and often unknown to the general public.

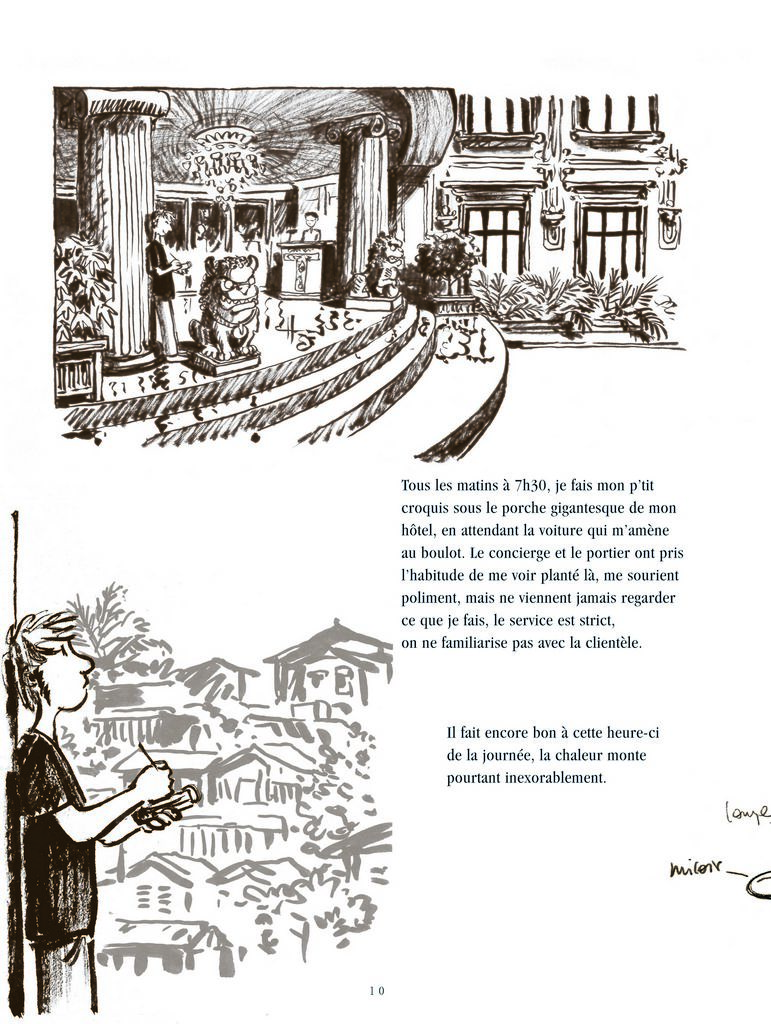

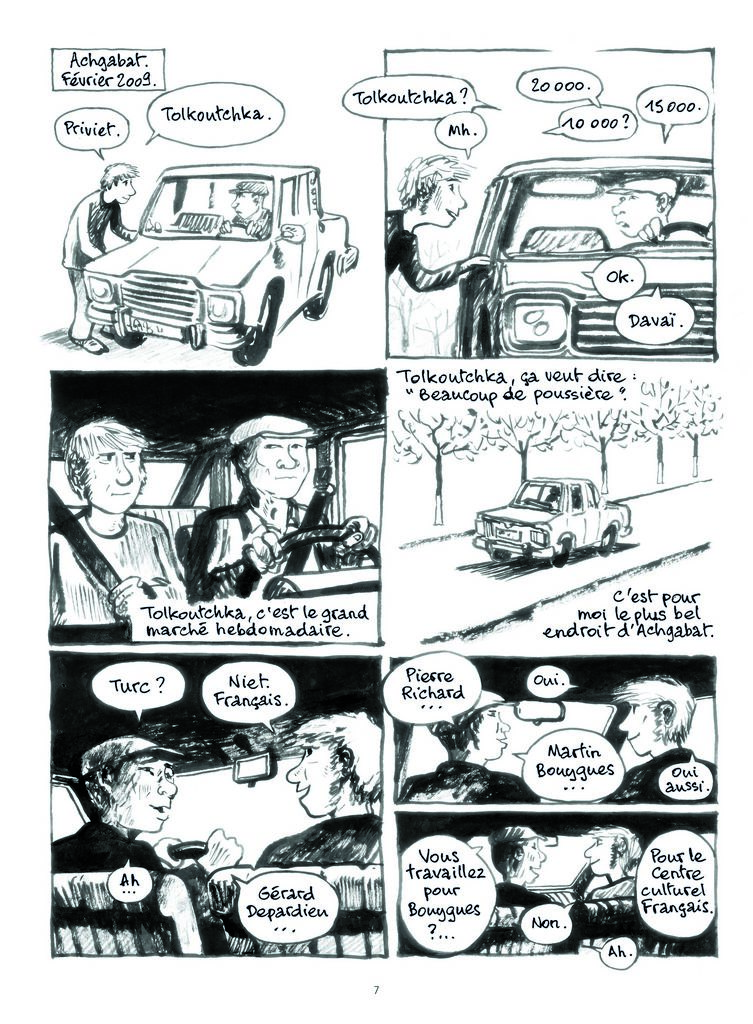

In the field, I draw and offer my sketches to the people I meet. It's a simple, fun way of getting to know people across the language barrier, almost like a little magic trick. Drawing awakens curiosity, creates a space for mutual understanding and enriches the relationship. In my comics, I try to capture precisely those moments when something happens, when an event takes shape.

In the Kingdom of the Kapokiers do you also draw children? What is it about these cultures that particularly appeals to you and makes you want to depict them in comics?

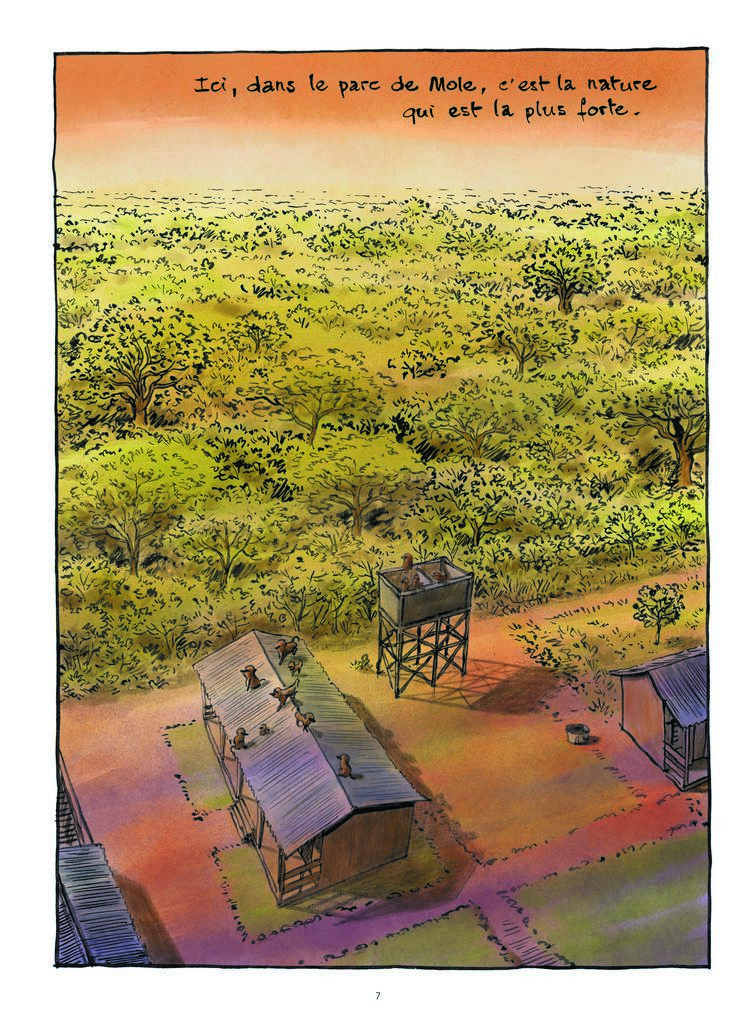

For this book, I was commissioned by the French NGO Elephants and men to attend environmental education classes for children living near the Mole National Park in Ghana. These schoolchildren were able to change their perception of wildlife, particularly elephants, which they had previously seen exclusively as a danger. The positive educational context (visits to the park, drawings, discussions) enabled them to acquire a wealth of knowledge about biodiversity, their environment, etc. and to take a different look at an animal that, surprisingly, less than 5 % of African children have ever met.

Your drawings often serve to listen and pass on information: how would you describe this role of intermediary?

I try to give a voice to people who don't have one, or not enough in my opinion. I collect testimonies, document ways of life and pass them on. My work is part of a documentary approach, guided by a constant attachment to reality.

Which of the First Peoples you have met have had the greatest impact on you, both humanly and artistically?

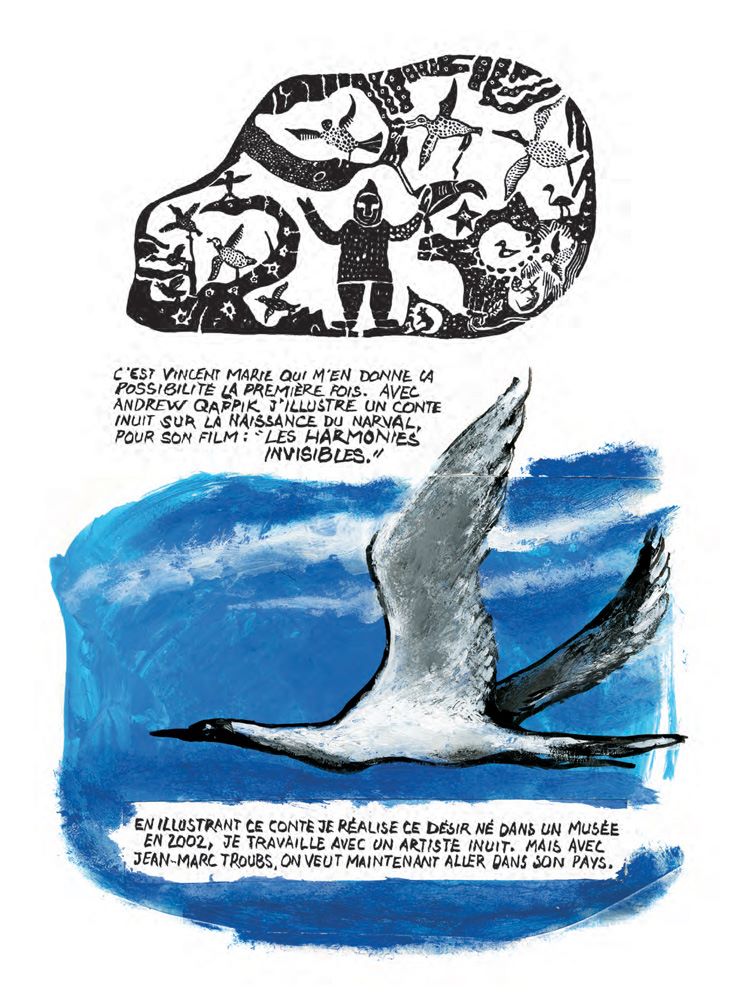

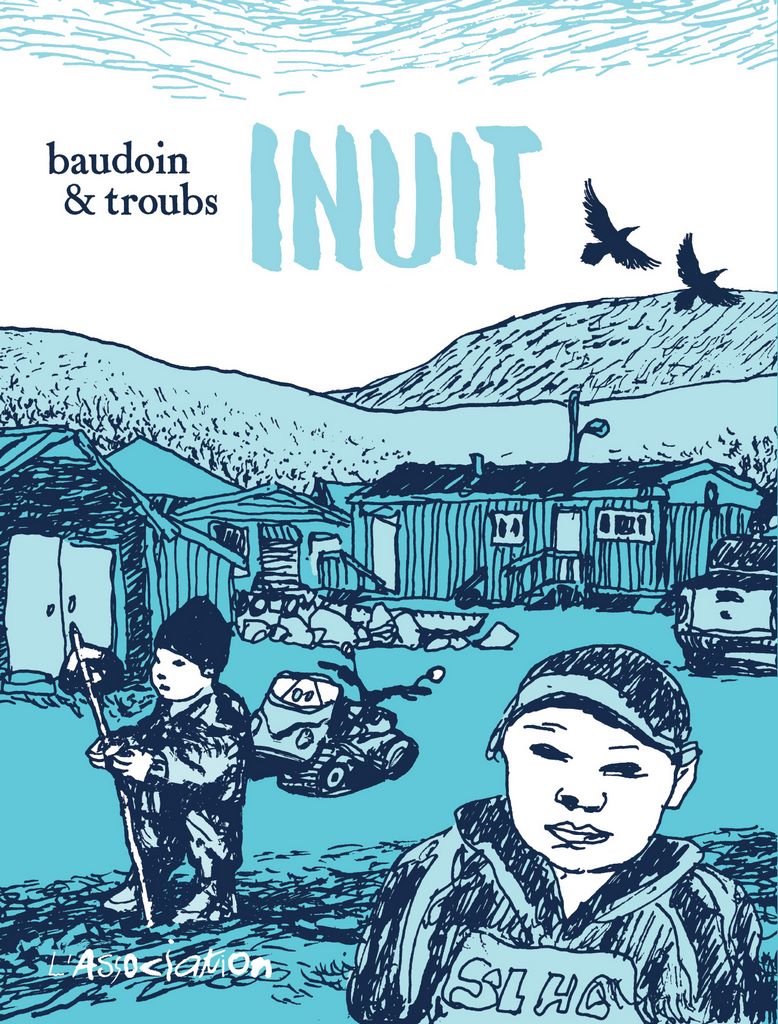

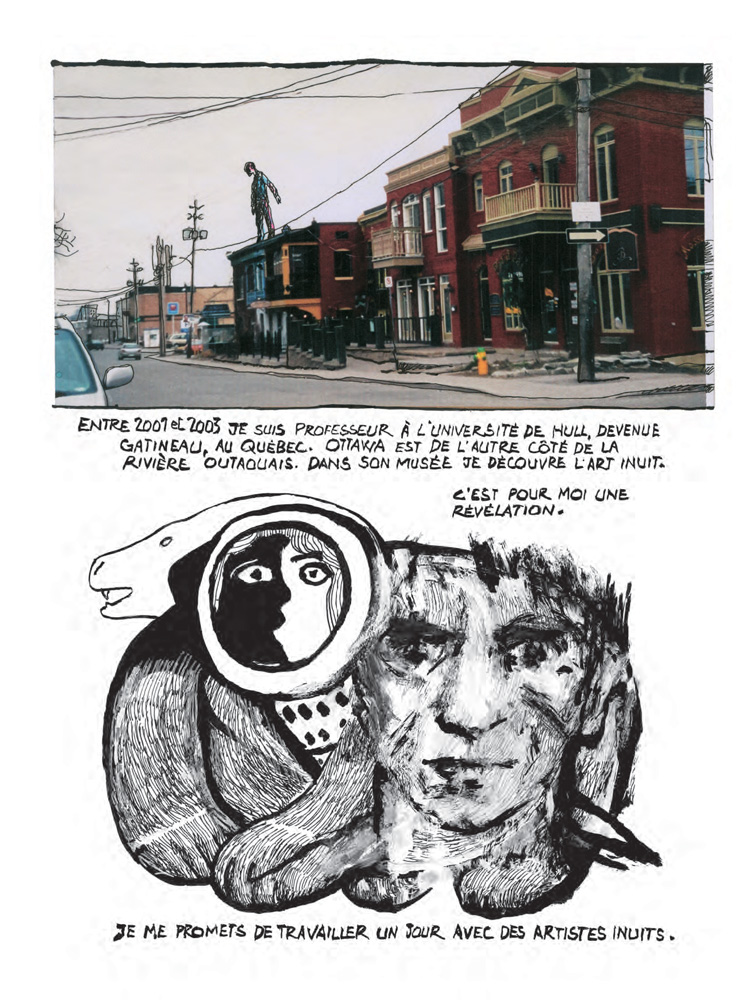

The Inuit people I met in northern Nunavut really touched me. I went there with my partner Isabelle Duthoit, who is a musician, and with Edmond Baudoin (1). We wanted to ask them about their relationship with art and their vision of the future, particularly in the face of the threats to their traditions in a context of rapid upheaval: sedentarisation, agreements with mining companies, drilling, climate change and so on. Lifestyles have changed radically over the last century.

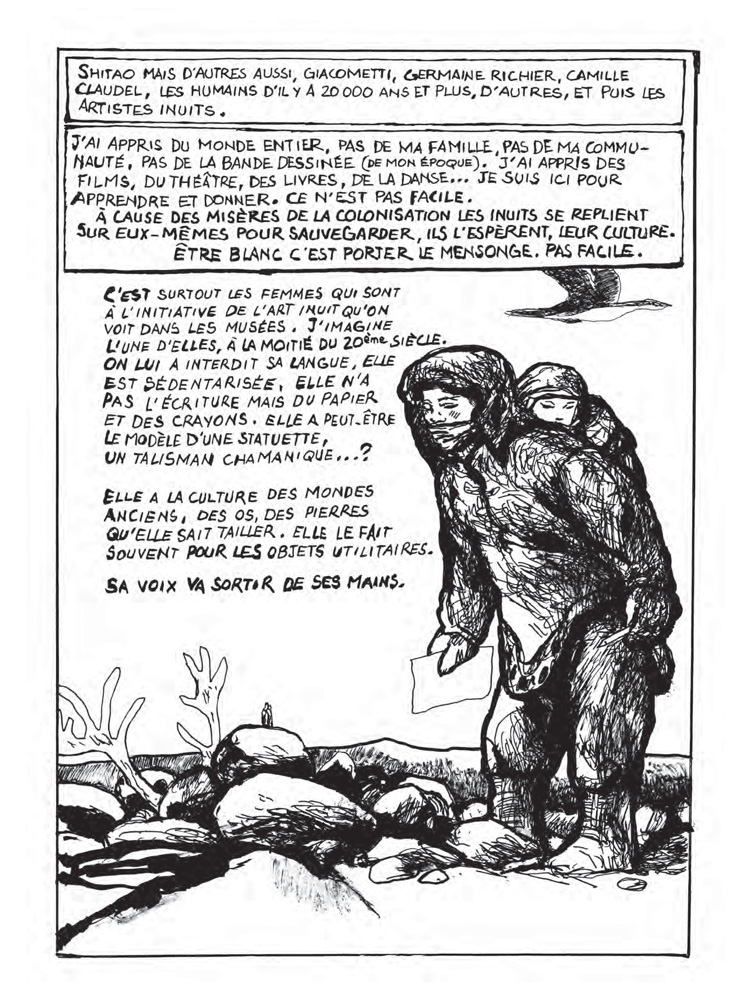

Forced sedentarisation and schooling have undermined many ancestral practices. One of the key questions they ask themselves is how to preserve identity, memory and tradition, while adapting to the contemporary world. Inuit artists continue to create by integrating modern media (drawing, comics, engraving), while drawing on their traditional symbols. For the Inuit, art is not seen as a separate practice, but is rooted in everyday life. Art is used to tell stories, pass on myths and knowledge, and keep a trace of things that are tending to disappear (traditional hunting, certain rituals).

We were also confronted with the complexity of the economic and political issues facing the younger generations. There is no such thing as a homogeneous Inuit people: some are educated, socially successful and benefit from mining royalties, while others live in extreme poverty. These peoples are not static. They face many issues: identity, culture, politics, the past and the future. Is mining a source of wealth? What impact does it have on the environment? How can we pass on the culture of our ancestors without betraying it? Ultimately, the same question runs through all these voices: how can we continue to be ourselves in a world that is changing so fast?

This questioning is not specific to the Inuit. It is similar among Australia's aborigines (2), who have no decision-making power when it comes to the big drilling companies. Some communities are trying to resist, but many no longer control their ancestral lands, no longer have access to sacred sites because of urban development, mining, infrastructure construction, etc., and complain that they do not have enough power over the decisions that affect their lands and traditions.

How do you approach the delicate balance between recounting their lives and respecting their privacy and their words?

It's never easy to go out and meet indigenous communities that have been and continue to be abused and despoiled in the past. We already have to ask their permission to use what they entrust to us, to trust them and to trust them in turn.

Among the Inuit, we tried to understand the thinking, mythology and cosmology of this people from the north of the American continent. Without forgetting to hear about the «difficult» cohabitation with the «Whites». We gathered a wealth of first-hand accounts from a variety of viewpoints, and listened to what the people we spoke to had to say. These people know their specific characteristics and their territory. We have heard their determination to defend their culture, a hope that they carry at arm's length and for which they are prepared to make any sacrifice. How to preserve identity, memory and tradition, while adapting? «Inuit culture is a way of life, of showing solidarity, of feeding ourselves with local resources».» says Rosie. «It's important for us to pass it on, to tell people how our ancestors lived here».», adds Eena.

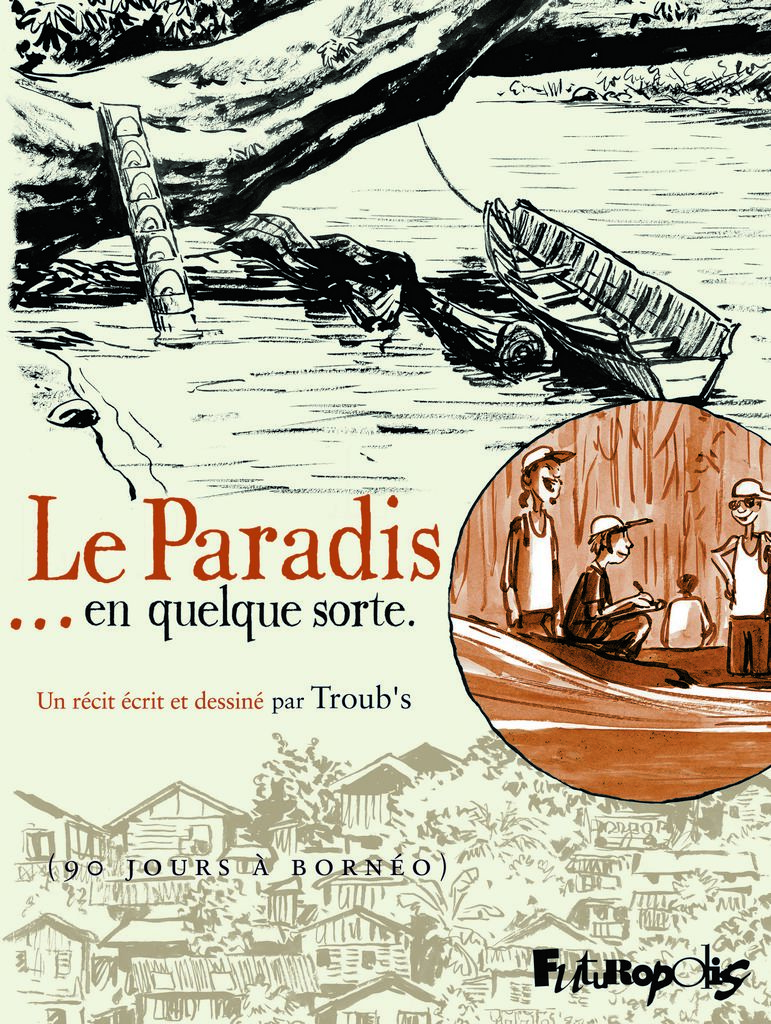

Sometimes we also have to overcome the language problem. For example, at Borneo, (3) for Dayaks, There are many complex languages. I took a pirogue up the Mahakam River and stopped off in various villages. I took the time to settle down, to immerse myself in the place, to live with the different tribes, to learn a minimum of vocabulary at each stage. I made myself a mini-dictionary with drawings. Exchanges are quick to develop, in fact. We share common rooms, our daily lives, we go hunting with them. It's important to stay for a long time to establish a relationship.

Did travelling with your partner make it easier for you to meet people?

Yes, although I don't always do it. Among the Inuits or in Ghana, the fact that we were accompanied by a woman made it easier for us to open the doors of families and make contact with other women. When you travel alone as a man, it's often tricky to approach women. On the other hand, as a couple, people feel reassured, especially in societies where roles and activities are strongly gendered.

Is drawing a medium that facilitates encounters and exchanges? How do people who aren't necessarily familiar with writing or who haven't studied react?

It depends on the place. Most people find it funny and amusing, but not everywhere. In Borneo, for example, the Dayaks were more interested in the paper than the drawings. They used to roll cigarettes with my pages of drawings that went up in smoke... Which goes to show that the value we place on things is relative. These are societies where we don't keep anything that isn't essential. What's more, the tropical climate is not conducive to preserving paper. Some people are also more interested in the pen than in what is represented.

On the other hand, creating portraits and depicting individuals has an almost magical effect. It impresses and demonstrates a real skill that commands respect. Particularly in Asian societies. The person who draws has a certain power.

Nature is omnipresent in your notebooks: what have the first peoples taught you about their relationship with the environment?

These people have a great respect for nature. They don't take more than they need. They know how to be reasonable so that nature can renew itself. They don't over-hunt to sell, just to feed themselves. One of their characteristics is that they feel part of the ecosystem around them. This is a great lesson for us.

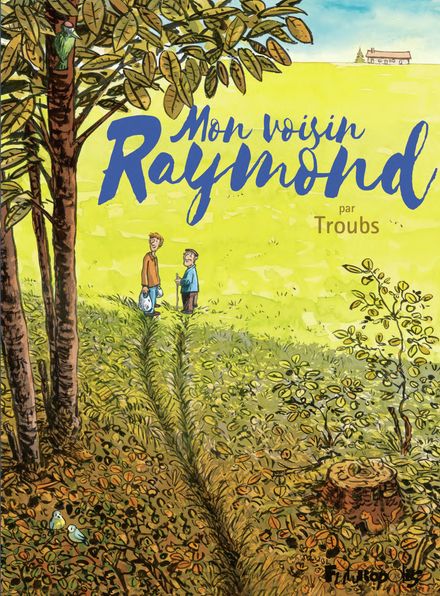

There are also people in the countryside who live in harmony with nature. I've produced a comic strip on this subject « My neighbour Raymond » (4). This octogenarian knew everything about his environment, his land and the people living within a 20 km radius of his home. He lived simply, to the rhythm of the seasons, in his small house surrounded by a garden and an orchard. He made his preserves, prepared his wood for the winter, went mushroom picking... A way of life rooted in the land, also found among many indigenous peoples intimately linked to their territory.

In your opinion, how can the worldview of indigenous peoples shed light on the current ecological crises?

Indigenous peoples see nature as a partner, not as a resource to be exploited. Trees, rivers and animals are all part of the same world, of which humans are only one element. Many live in small groups, organised around solidarity and sharing. This model promotes human-scale societies, capable of self-regulation, limiting their needs and preserving their equilibrium. Accustomed to sometimes harsh or changing environments, these peoples have developed a great capacity to adapt. In this respect, the Inuit often told us that they could easily adapt to climate change, whereas we in the West could not, because we have developed a dependence on networks (energy, transport, globalised food). When these systems are weakened by a climate crisis, individual adaptation is much more difficult. What's more, many of the skills associated with self-sufficiency (cultivating, repairing, managing water, living with little) have disappeared or been reduced in the Western world, whereas they are still alive and well among these peoples. Because of their closeness to the land and their culture of adaptation, indigenous peoples are often more resilient.

Drawings have a particular power to bear witness. What can comics do that a text alone or a photographic report wouldn't?

Comics reach a wide audience, young and old alike. Today, they are widely used to convey strong messages, whether political, social or topical. A sketch, a portrait, can sometimes express more than a photo: they leave room for interpretation and emotion, and also reflect the viewpoint of the cartoonist. This assumed subjectivity creates a porous space between the model and the artist, opening up the possibility of delving deeper into a person's character and recreating a more intimate atmosphere.

Comics also allow several registers to be intertwined: narration, drawing, documentary and poetry. It gives the reader time, inviting them to stop and take in a frame, to feel an atmosphere, to enter into a story gradually.

At festivals, I meet readers who confirm the interest of my books. I'm just a go-between, but these stories can raise awareness and inspire people to take action. The strength of comics lies precisely in making accessible experiences or visions of the world that might seem remote, by embodying them in faces, gestures and messages.

Do the people you have drawn ever discover your books?

Yes, in Ghana and Borneo. I don't necessarily get any feedback because the distance and lack of resources make it difficult to exchange ideas. But a book stays with you. It's passed down from generation to generation. It's a living memory.

What will your next trip be?

I'm planning a trip to India to visit the Adivasi communities who live in the forests and are persecuted. They are fighting against state repression and extractivism.

What do you remember most about drawing or meeting someone?

Among the Mahafaly of Madagascar, an ethnic people from the south-west of Madagascar who live in very arid regions; they are pastoralists who live in small scattered groups, clan-like, with their zebus. We drew portraits, animals and zebus in the sand. Those were great moments that I'll never forget. The drawing has faded but the memory is still very vivid.

1 - Inuit, comic strip by Baudoin & Troubs published in 2023, which recounts their trip to Labrador and Nunavut, and Nunavut, a graphic essay published on 4 June 2024 by Éditions L'Association.

2 - Walkatju, Editions Alain Beaulet and Penser Parallèle, Editions Rackham.

3 - Paradise... of sorts. Published by Futuropolis.

4 - Mon Voisin Raymond. Published by Futuropolis.

Interview by Brigitte Postel