There are places that you don't pass through. You stay, you linger, you return. Salies-de-Béarn, hemmed in by the meandering Saleys river, is one of them. This small town in the Béarn region, whose name seems to ooze salt, welcomes you with the gentle, patient manner of towns that have nothing left to prove.

Table of Contents

As you arrive, you are seized by a feeling of deep-rooted calm, as if the centuries had slowed down here to the pace of a pilgrim or a literate stroller. The light plays on the half-timbered facades, the murmur of the salt water seems to whisper forgotten chronicles, and the neo-Moorish thermal baths watch over the cure of bodies and souls like discreet sultans.

There's no modern din here, just the echoes of voices, perhaps that of Henry IV on his way to Navarre. Salies is like a fountain of history, salty of course, but also warm and deep.

The Bayaà crypt

Situated beneath the main square in Salies-de-Béarn, this former open-air well was covered by a vault in the 19th century. The removal of the salt water and major works have now made the crypt accessible to visitors. The play of light highlights this remarkable construction. It's also an opportunity to learn about the history of salt water mining over the last 3,000 years.

© Béarn de Gaves Tourist Office

An old man in the arcades of the Place du Bayaà - a word that only a native knows how to pronounce from the heart - told me about the Jours de Sel (Salt days) and the Confrérie des Culs Blancs (Brotherhood of White Asses), guardians in their own way of a treasure older than Gascony itself. I saw a tiny Republic, faithful to its ancestral laws, where salt is not just a commodity but an identity.

The narrow streets always lead down to the river, as if everything here converged on this trickle of water that was once white gold. Salies was born of a geological miracle, but it grew out of a human pact. And in this tranquil landscape, I discovered the taste of salt and the fragrance of silence.

The Boar and the Salt: a local parable

It is often said that great discoveries are born of chance. In Salies-de-Béarn, fortune came from... a wild boar wounded while hunting.

The scene takes place somewhere in the Middle Ages, but the place is already imbued with the earthly alchemy that bubbles up underground with a wealth unknown to man. Hunters are stalking a wild boar in the nearby forest. The beast is hit, collapses not far from what was then an unglamorous marsh, and its pursuers find it after a few days - its body already covered in white crystals and partly preserved.

A miracle! Or rather, natural chemistry. The mud in which the boar expired contained salt. And this salt, both antiseptic and sacred, had preserved the flesh of the beast. Where putrefaction would normally have done its work, time seemed to stand still.

This wild boar, an animal lying on the ground, was to become a founder. Like the she-wolf in Remus and Romulus, the Salies wild boar was more than just prey: it was almost a miracle.

Men were intrigued and explored this marshy land, discovering underground salt springs. This was the origin of Salies, from the word " salis ", salt, the white gold before sugar. The town was built not far from there, with a salt works at its beating heart, feeding the economy, politics, gastronomy and even local institutions.

Nestling in a corner of the Place du Bayaà in Salies-de-Béarn, the Fontaine du Sanglier dates back to 1927. This fountain, with its sculpture of a boar's head, has become the town's emblem. And as wise people know how to recognise what they owe to the gods or to animals, the people of Salies immortalised the boar on their coat of arms: a proud, bristling suid, framed by the motto of the Béarn region:

"Si you nou eri mourt, arres n'béyé quéu aü" ("If I hadn't died, no one would be living here").).

A simple phrase, but with an ancient, almost biblical force.

© Béarn de Gaves Tourist Office

In this anecdote, a wise man would have seen more than a tale: a metaphor. Salies-de-Béarn was founded on an act of hunting and also on a respect for the natural miracle, on an economy of salt shared between families, recorded by brotherhoods and perpetuated in rituals.

And in the streets of Salies today, between two half-timbered houses, you might come across a small boar carved on a wall, a bench or a fountain. As if in recognition.

Les Parts-Prenants: the notaries of salt and memory: A salty legend

If it is true, as wrote the historian Fernand Braudel (1902-1985), who studied rural France, that every village in the south of France still has a thousand-year-old political organisation, so Salies-de-Béarn is a small salt republic, and its Confrérie des Parts-Prenants, a Senate of deep waters.

Salt isn't just a condiment here: it's a foundation, a constitution, a common good. Ever since the miracle of the wild boar - the corpse sanctified by the salty mud - the town has built its order around this subterranean wealth. But unlike individual or feudal fortunes, the salt of Salies was very soon everyone's business.

This is where the Parts-Prenants come in. First established in the 13th century, these hereditary members formed a community of undivided owners of the salt deposit. A closed but stable community, handed down from generation to generation, by blood or by name. The watchwords: joint ownership, solidarity, continuity. Each share is passed on, not sold, in an almost feudal logic, but without a lord. For in Salies, salt reigns supreme.

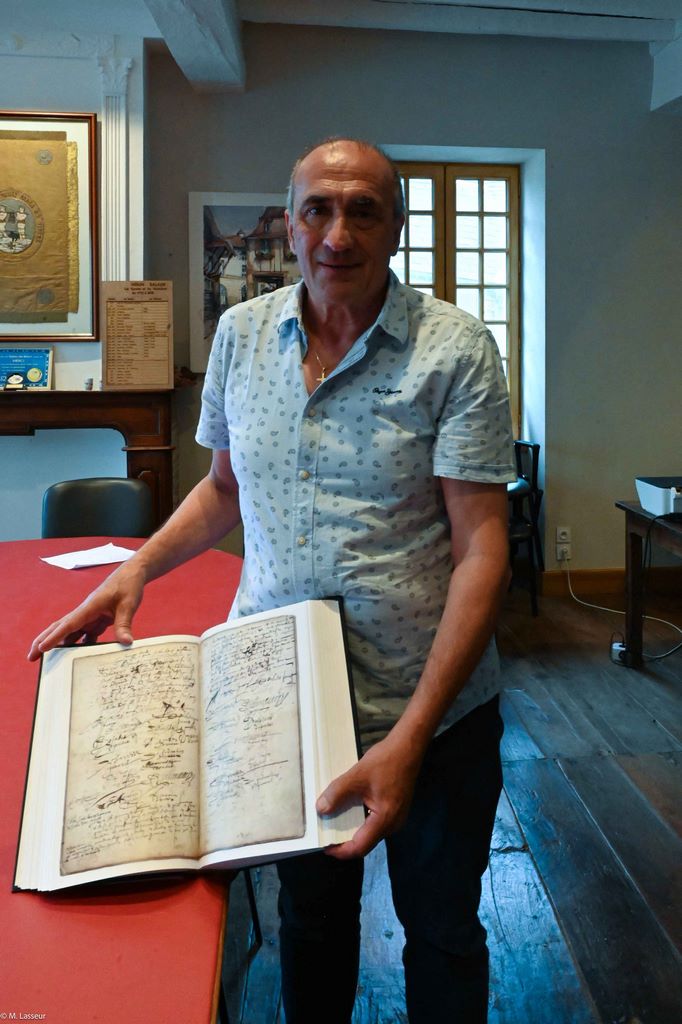

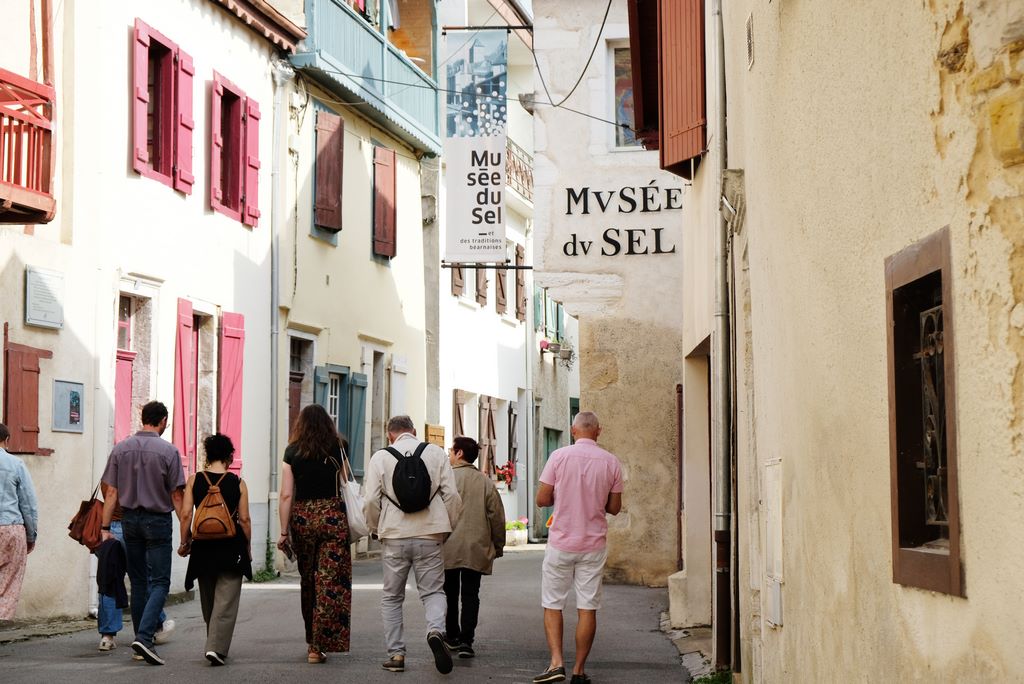

The Salt Museum, discreet but solemn building, houses their archives, their decisions and their secrets - like a small secular Vatican where the underground treasury is administered. Everything here is codified: who can be a Part-Prenant, how dividends are distributed, how often the fountains shed their salty tears.

And like all ancient communities, the brotherhood has its rituals. Every year, during the Salt Festival, they parade in traditional costume, dressed in white (hence the nickname "White Asses"), girded in red, sometimes holding a symbolic cane or a document yellowed by time.

Where other towns celebrate their patron saint, Salies honours its salt - and its guardians. It's a secular procession, to be sure, but one with an almost religious fervour. As the Parts-Prenants pass by, you can sense a form of attachment stronger than the law: a bond of flesh and soil, of memory and matter.

This institution could be seen as a miracle of republican longevity: a model of shared economy, where wealth is neither speculated nor squandered, but protected as a sacred common good, like the waters of an oasis.

And at a time when the world is buzzing with individualism, Salies is keeping its property safe, in a form of gentle, stubborn loyalty. For as the motto proudly inscribed at the heart of the town puts it: "Who has salt, has life". . And in Salies-de-Béarn, it's the Parts-Prenants who look after them.

The benefits of a relaxing, salty break

Salies-de-Béarn is also a town of water. But it's not water you drink. It's water that stings, water that bites. It comes out of the ground laden with salt and it has the character of salt: brutal, conservative, tenacious.

People don't come here for the scenery, however beautiful, or for the sun, however generous. No, they come for the treatment. That's what the brochure says. But I wanted to know what is really being treated at Salies. The therapeutic properties of Salies-de-Béarn thermal spring water have been proven in the treatment of a wide range of conditions, including endometriosis, menopausal problems, rheumatic pain and enuresis in children.

The first thing I notice is the silence. At the spa, you don't talk much. You soak, massage and sweat. The staff are gentle, almost religious. One nurse said to me: "We treat pain, but not all pain". .

I sat on a bench near the salt jets. A woman in her forties was reading a magazine without turning a page. A man with a high belly and slicked-back hair was chatting away without listening. I finally understood: pain is a facade. Visitors to the spa arrive with backache, leave with a clear complexion and sometimes a lighter heart. This isn't a hospital, it's a stopover.

In the bathing corridors, doors slam softly. And under the bathrobes, which are sometimes too white, you can feel the scars of other pains: loneliness, regrets, small ordinary failures. I met a doctor. He told me about sodium, calcium and osmotic pressures. I asked him what he thought of his patients. He smiled: "They're people like anyone else. But here, they have the right to admit they're tired"..

Then I understood. Salies-de-Béarn is not a spa. It's a secular confessional for tired souls. People come here bent over, and sometimes leave straighter. Is it the water that does it? A psychoanalyst would have said: "I saw in the steam of the thermal baths what France keeps silent about: people who are no longer in pain, but who need to be touched. "

And let me tell you: at Salies, you don't always get better. But you do get a real rest.

Tourist Office of Salies-de-Béarn

8 bis Pl. du Bayaà

64270 Salies-de-Béarn

https://www.tourisme-bearn-gaves.com

Salies-de-Béarn saltworks operating company

Avenue des Salines - Herre district

64270 Salies-de-Béarn

05 59 65 62 29

Text : Michèle Lasseur