Butō is a contemporary dance form founded in the 1960s by Japanese dancers Tatsumi Hijikata (1928-1986) and Kazuo Ōno (1906-2010). Hijikata created a transcultural, transgressive and revolutionary form of expression, rejecting institutionalised artistic styles, but sometimes referring to his cultural heritage. He called his art ankoku butō or dance of darkness.

Table of Contents

During this period, from the second half of the 1960s to the early 1970s, Japan was trying to recover from its first defeat in over 2,000 years of history. Bruised by the tragedy of Hiroshima, society aspired to Western modernity, while at the same time being prey to confusion, the violence of student movements and the advent of the underground that permeated Tokyo's performing arts scene. It was in this context of protest and artistic ferment that Hijikata invented a cosmogony that challenged the values of the modern consumerist world, creating a dance in which the body is a sacrificial body, where the taboos of death and eroticism are at the heart of this antidance (1), where "the antagonism between life and death is expressed in an intense and concentrated way".he says. His first choreographic work, Kinjiki (1959), a homosexual ritual, was an earthquake and scandalised some of the public, homosexuality still being a very taboo subject in Japan. With his head shaved - a practice later adopted by butō dancers - his torso and face painted black, dressed in grey trousers and barefoot, Hijikata enters the stage running in a circle. He holds a chicken and joins a pale-skinned young ephebe dressed only in briefs (Oshito Ōno, the son of dancer Kazuo Ōno). This chicken, symbolising sex and the sacred, ends up strangled between Oshito's legs. While the second half is played out in total darkness where we can make out the bodies rolling around, and the audience hears erotic moans and "I love you's" shouted by the dancer. Ten sultry, powerful and fascinating minutes that would launch the work of Hijikata and generations of butō dancers.

The raison d'être of butō: the body

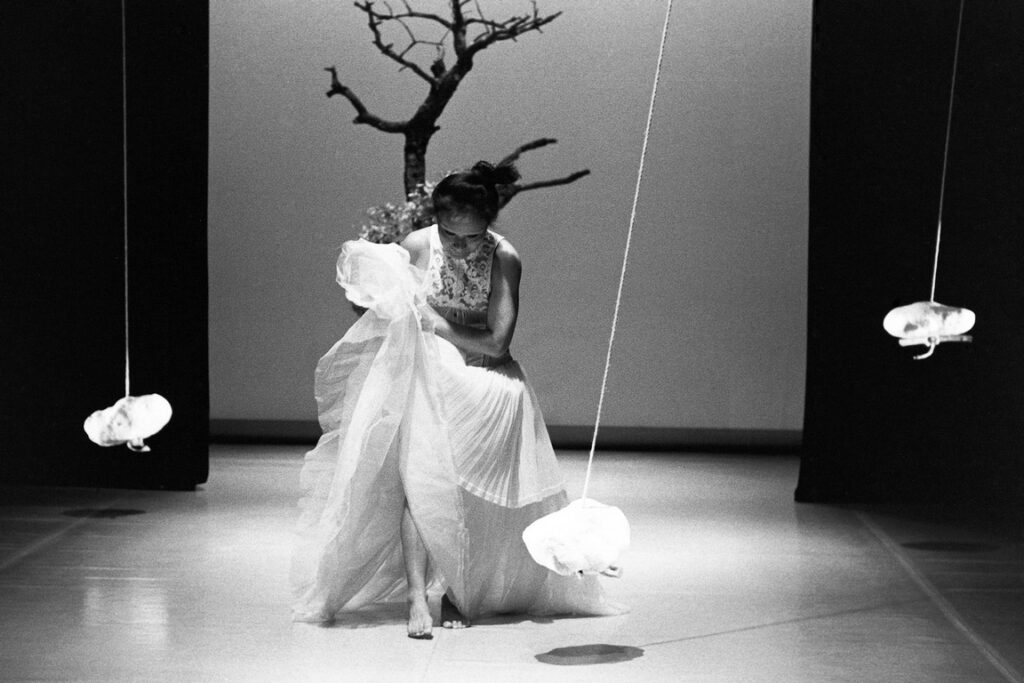

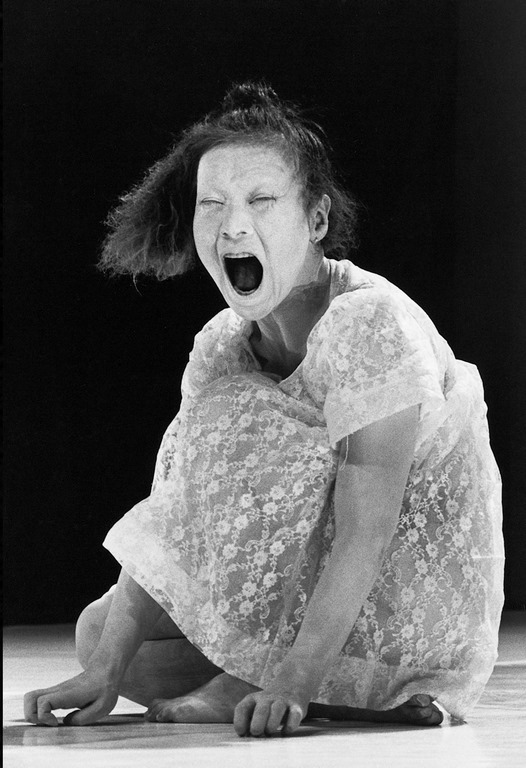

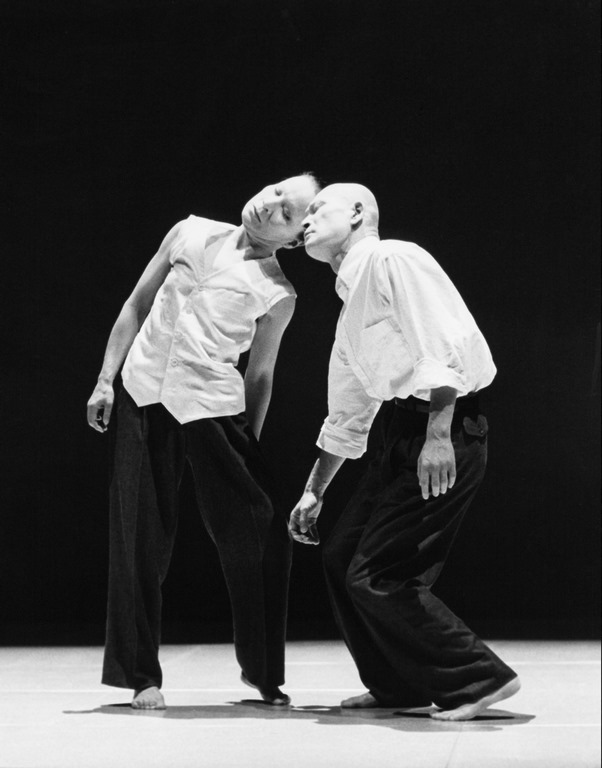

This choreographic form is close to performance. It carries with it something excessive, obscene, extravagant, fascinating and poetic all at once. Rejecting all stereotypes, Hijikata, his friend Kazuo Ōno and their students (Yoshito Ōno, Yōko Ashikawa, Akaji Maro and Kō Murobushi among others), present on stage the uncomfortable experience of the introspective work they carry out on themselves, exposing to the public gaze their bodies traversed at once by animal impulses, slow and spasmodic movements, intimate suffering and black beauty. Bodies that can be described as "Seismic. All the energy of the dancers is concentrated in minimalist movements, a very slow walk, a stiff and tense body, the prototype of the male body in the butō. In his creations, Hijikata develops an aesthetic that encompasses ugliness, deformity, fright, images of death or illness, mixing the erotic and the abject, the masculine and the feminine, the dark and the luminous. In total collision with the theatrical act and the narrative surrounding Japanese identity. His dance, he said, "extends the concept of "human. I base my dance on the discovery of the possibilities of metamorphosis of the human body into everything, including animals, plants and inanimate objects".. Inspired by the writings of Jean Genet, Antonin Artaud, Sade and Georges Bataille, and drawing on the traumatic sources of his rural childhood, he made the feeling of alienation and strangeness he felt when he landed in Tokyo - passing for a hick and a poor dancer in the eyes of those who didn't understand his originality - the basis of his artistic work.

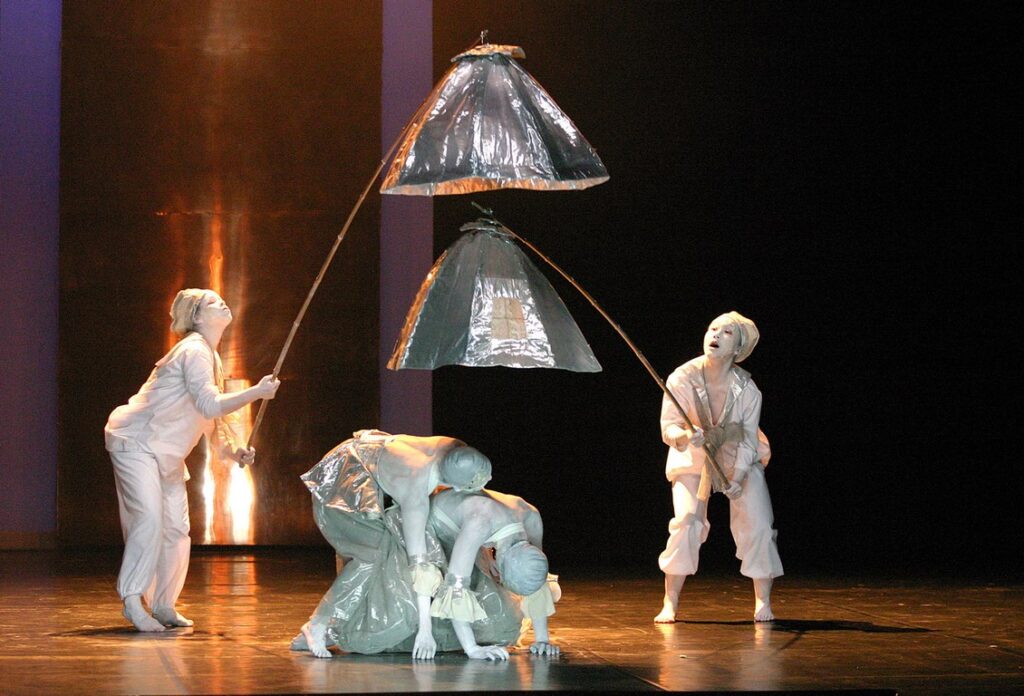

"A sacred technique

A marginal artist, tough and very demanding, going so far as to bully his dancers, "Hijikata will consciously use the heritage of outcast artists (2) to concentrate the transformational power of his art.reveals Kuhihara Nanako (3). After the experimental butō of his beginnings, in which he smeared black grease on his torso and face, he used white make-up for the bodies: shironuri make-up (painting oneself white), present in kabuki and also in older theatre. This white make-up, a symbol of the sacred, death and femininity, has become a feature of butō, and is the edge that both outlines and abstracts the real body. "Nudity is probably the ideal way of emphasising the importance of the directness of the body. However (at the same time, I repeated the importance of distance), the nudity of the shironuri doubles the distance between normally clothed civilisation (laws, system, morals) and the glorification of the body itself (body-building, group exercises, jazz dance, disco dance, etc.) which is a fascist tendency."says dancer and choreographer Kō Murobushi (1947-2015). The dancer brings with him a provocative aesthetic "It is a sacred technique that assimilates antagonisms. It is a sacred technique that assimilates antagonisms".he sums up.

There is also the work on the face and eyes found in nō theatre, where the actor performing without a mask can make his face look like a mask. Dancers can close their eyelids, roll their eyes back or squint (which in Japan evokes spectres or death) to show the whites of their eyes, an attitude used in the style aragato (rough), an acting style from Kabuki theatre.

After 1973, Hijikata stopped performing and devoted himself to directing until his death, concentrating on the intimate and fundamental aspects of his art. He developed a body of techniques that are still used today by butōka (butō dancers). Gifted with great charisma and a "power of bewitchmentAccording to Kō Murobushi, he teaches his dancers a way of being in their own bodies, awakening them to their own sensations so that they can express themselves. "a powerful presence that is transmitted intensely to the audience. The choreographer forces the body to become empty of everything that attaches it to the outside world. The body is then ready to move, to translate what is experienced in the interior of the being. "I don't try to explain it, I know it exists, I live with it... It is perhaps this wave that is the movement of my dance".says dancer and choreographer Carlotta Ikeda (4). The mind can finally wander and let the body express itself. Waiting for the end to come or a suspended moment? The spectator no longer knows. They too are waiting, holding their breath, captivated by the powerful presence of the dancer or dancers. The dancer moves very slowly, seemingly in a trance. The air is held for a moment, then a cry or a giggle bursts out. There is nothing to understand that is not already there. "The spectator must be transformed by the experience, as in a ritual"., says Hijikata.

Training dancers is difficult, sometimes painful, and its aim is to radically question the body, to bring it back to a state that precedes learning. The aim is to bring them to a deep awareness of their physicality before beginning any movement. They need to concentrate on their inner perceptions and not be preoccupied with appearances. Controlling all their muscles, making their back muscles undulate, practising various types of steps, moving forward on tiptoe, gliding imperceptibly over the floor, remaining motionless while making micro-movements, etc. Unlike Western dances, the butoka body is involved in its entirety, organically, emotionally and physically. "Butō starts from what can only stand still, from what all dance has declared impossible. Butō dancers listen to a suffocating lullaby in a cradle burning with flames."explains Kō Murobushi.

Kō Murobushi, one of the main inheritors of Tatsumi Hijikata's original vision

" When I saw Hijikata danser en 1968: Hijikata Tatsumi et les Japonais: Révolte de la chair (Nikutai no Hanran) (5), it was a total shock. It was the first time I'd seen something really new. It was the first turning point in my life and I decided to become a butō dancer. In Japan, we say that in life, there are two opportunities to change, to tip over. This was the first.he confided to me after a performance. In this show, Hijikata enters the stage on a palanquin, then dances naked, frenetically, shaking with spasmodic movements, with a golden phallus and a tuft of false hair hanging down, reminiscent of an extract from Antonin Artaud's Héliogabale ou l'anarchiste couronné. Having eliminated all fat from his body by fasting for two months before his performance, his muscles and veins protrude from his body. At the end of the performance, Hijikata ties himself up with ropes and is hoisted above the stage, like an inverted Christ. The audience was spellbound and gave him a standing ovation.

Murobushi worked with Hijikata for some time, then founded the butō group "Dairakudakan" with Akaji Maro (who continues to perform) and Uhio Amagatsu (founder of the Sankai Juku troupe, which developed a sophisticated theatrical style). Then, in 1974, he created the women's company "Ariadone" with Carlotta Ikeda (1941-2014), another major figure in butō. After founding the men's butō group "Sebi", with Ariadone he introduced butō to Europe and contributed to its worldwide recognition with Le Dernier Eden - Porte de l'Au-Delà, which was a masterly success in Paris in 1978, followed by an extensive tour across Europe in 1981-1982. With her own all-female group, Ariadone, Carlotta Ikeda took it upon herself to dance naked, which was seen at the time as an attack on the morality of Japanese society. Many of her creations have been danced all over the world, where she reveals her art of metamorphosis with such refinement.

As a faithful heir to Hijikata, Murobushi will continue his research and perform alone most of the time. A tireless traveller, running from one continent to another, he would amplify this darkness (yami) (6), the foundation of his bodily explorations. Every gesture is approached in a double movement of death and rebirth. "In my show, I always try to show a death that was able to live, and what is reversibly interchangeable in life in death. Most likely, my dance shows this chain (illness, death, ecstasy, madness, temptation, passion, love...) that is directed by darkness." Ko Murobushi refuted the butō show. The butō is not a show," he told me. Some very famous troupes protect themselves with sets and sophisticated staging. I hate that kind of butô. It is too far removed from the original butō as founded by Hijikata and as I practise it. I refuse to take on a dancer who doesn't take risks. You have to learn to die in dance. To be alive at the same time as being a rock, a flower or the shadow of your own body. The ideal transformation would be to become something that doesn't exist, and to become nothing, you have to transform yourself into everything.

Notes

(1) In a country renowned for its erotic art, until 1995 it was forbidden to show hair or a naked body in photos or live, with the sexes being blacked out even in imported magazines.

(2) During the Edo period (1603-1868), kabuki and its performers were held in low esteem and assigned to particular districts that corresponded to the pleasure districts. It reached its apogee in the 18th and 19th centuries and was at the heart of popular culture. It was during this period that acting troupes took shape, gaining social visibility and organising themselves into families that have perpetuated their styles and repertoires to the present day. Attempts at censorship and discrimination continued until the Meiji era (1868-1912), because kabuki signified resistance to the established order and power through behaviour deemed anti-social, marginal or heretical. It portrayed a transgressive world seen as a threat to society, with suicides, erotic tableaux combining sex and death, demons and ghosts.

(3) The Strangest Thing in the World, a critical analysis of Hijikata Tatsumi's butōKuhihara Nanako, Les Presses du réel, 2017.

(4) Interview by Stéphane Vérité for the presentation of Waiting in 1997.

(5) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hNV0T5zI7VI&list=PLsAlwxLtUODS8uG0RPix-q6CE1s9qAAx-&index=6

(6) "In Japanese, the word " yamai (disease) is linked to yami (darkness)" or " yama (mountain)". "yamai" makes us look into the abyss of death; it shows us the unknown and invisible part between life and death and brings us closer to what is considered "yama", the realm of the dead, in Japanese mythology"., explains Ko Murobushi.

Read

Hijikata Tatsumi Thinking An Exhausted BodyUno Kuniichi, Dijon: Les Presses Du Réel, 2017.

Carlotta Ikeda, Butō Dance and beyond, Photographs by Laurencine Lot, Ed. Favre, 2005.

Aesthetics of Impossibility, Katja Centonze, Ed. Cafoscarnina, 2022.

Frapper le sol avec ses mainsTatsumi Hijikata sur la voie du butō, Cécile Wagner, Actes Sud, 2016.

Text: Brigitte Postel

Opening photo : Laurencine Lot

This article appeared in Natives n°13 https://www.revue-natives.com/editions/natives-n13/#extraitnatives