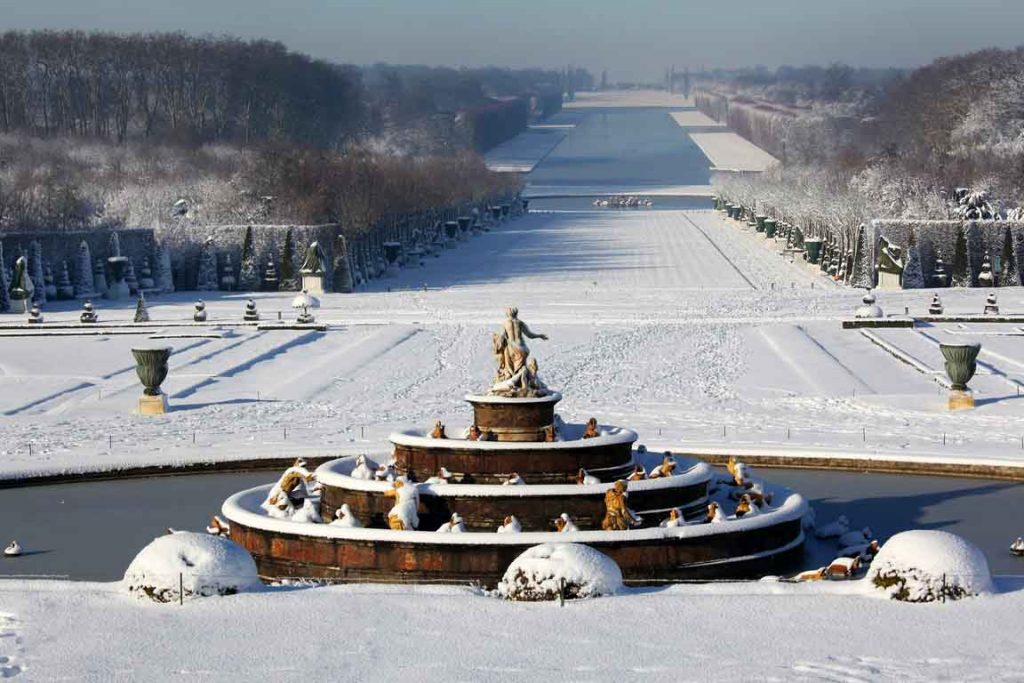

It's rare to see the gardens of the Château de Versailles in the snow. The stone and marble statues are wrapped in a green blanket, the foliage bends under the weight of the snowflakes and the topiaries are covered in white. Take a stroll through this setting so beloved of the Sun King, which has established itself as a masterpiece of 17th-century French art.

If the gardens of Versailles have become the symbol of refinement and perfection thanks to the talent of André Le Nôtre (1613-1700) eAlthough the gardens were the work of his gardeners, they were first and foremost the brainchild of Louis XIV. Through the organisation of the space, the choice of statues and ponds, and the design of the groves, the King created a work that reflected his political, aesthetic and philosophical ambitions.

As soon as the snowflakes cover this wadded-up setting, the décor is transformed into a living theatre, with bronzes emerging from their white gangue. The yew trees become the guardians of the wide esplanades and the water beds, mirrors frozen in light. In this temple enamelled with symbols, some of which are concealed beneath this virginal cloak, the hornbeams lining the alleys stretch out their white-gloved arms and the trees form ephemeral cathedrals.

The Palace of the Sun King

You might think you were in the palace of the Snow Queen. But we are in the palace of the Sun King, Louis XIV - Apollo - as he appeared in the ballets at the beginning of his reign. A jewel intimately linked to the will of a king, Louis XIV, and the talent of his architect-gardener, André Le Nôtre. After the splendid Vaux feast given to the King by Fouquet on 17 August 1661, Louis XIV, piqued by jealousy, wanted even more sumptuous gardens than those of the Superintendent of Finances. The work, undertaken at the same time as the palace, was to last some forty years.

Built according to a rigorous plan, the gardens are arranged around two main axes - the North-South axis from the Bassin de Neptune to the Pièce d?eau des Suisses ? and the East-West axis from the façade of the Galerie des glaces to the end of the cross-shaped Grand Canal.

Hidden symbols

Hypnerotomachia Poliphili by Francesco Colonna, published in Venice in 1499, undoubtedly influenced the initial design of the Gardens of Versailles. But the final result is more than a simple décor inspired by ancient art and love, or a reminiscence of an antiquity that has disappeared forever, as signified in Poliphilo?s Dream by the omnipresence of ruins. But there are no ruins at Versailles. Quite the contrary. The King poured all his genius and that of the scholars of the time into his Gardens to create the symbolism he defended. Men of letters and science, philosophers, artists and theologians all contributed to this achievement, which can only be explained by its purpose: the spiritual life to which the King invites us through esoteric messages scattered throughout the gardens.

From Ponds to Groves

André Le Nôtre did not work alone to develop the site, which covered more than a thousand hectares at the time. Jean-Baptiste Colbert, Superintendent of the King?s Buildings from 1664 to 1683, oversaw the project. As early as 1661, the first Allée d?Eau, the parterres du Nord and du Midi, the Parterre d?Amour and Le Vau?s Orangerie were completed.

The Bosquets appeared in 1663: Bosquets du Dauphin and de la Girandole, then in 1666, for the education of the young princes: the Labyrinthe with its 39 fountains inspired by Aesop?s fables (now disappeared, it has been replaced by the Bosquet de la Reine). The Bosquets to the south were joined by their northern counterparts: the Théâtre d?Eau and the Bosquet de l?Etoile. The campaign to create the Bosquets continued for around twenty years: Bosquets du Marais 1671, Pavillon d?Eau and Berceau, which became the Arc de Triomphe and the Trois Fontaines.

In 1674, the Salle du Festin, the Bosquet de l'Encelade - the giant struck by lightning - and the Bosquet de la Renommée were completed. Their symmetrical counterparts are the Galerie d'Eau, the Bosquet des Antiques and the Bosquet des Sources.

In 1683, the death of Colbert and the growing importance of Louvois led to the disgrace of Le Brun, who was replaced by the minister?s favourite, Jules Hardouin-Mansart, much to the fury of Le Nôtre. The Bosquet de la Renommée was replaced by the Dômes, and the Bosquet des Sources gave way to Hardouin-Mansart?s Colonnade, which was strongly criticised by Le Nôtre.

Until his death on 1st September 1715, after 54 years of reign, this gardener-king never ceased to lavish the most attentive care on his work, which can be read as his spiritual testament.

A will to decipher

What is so precious about these gardens? What do they reveal to the visitor? Here, aesthetics compete with substance, myths and legends with history. Allegories, mythological figures, symbols and fountains create a mysterious dialogue that arouses curiosity and prompts us to wonder about the intentions of its creator.

Why are these statues, all rigorously aligned, nevertheless placed in an apparently illogical order? Why is the sun's path depicted in reverse, i.e. from west to east? And why are the gardens structured in tiers that rise in a pyramid shape to the top where the castle stands? Esoteric, hermetic, alchemical, evidence of a time when mankind wanted to be in direct contact with the mysteries of the universe, the symbols are waiting to be deciphered. Here are a few examples, including the basins of Neptune, Latone and Apollo.

The Neptune Basin

The god of water, Neptune embodies the power of the oceans. When he uses his trident, the waters are unleashed, forming gigantic waves that sweep away everything in their path. Does this Basin, the largest in Versailles, symbolise the belligerent and destructive forces that confront us all?

The Latone Basin

Let's go down the first flight of steps to Latone. From this vantage point, so dear to the King, you can see the Bassin d'Apollon, the Grand Canal and the park in the distance.

This park is a bit like nature in its raw, almost savage state, the forests where the King liked to shoot deer. The profane world, as it were. The gardens and groves, on the other hand, are ordered and subtly designed by the man who decides their composition. It's "chaos sorted out", notes Jean Erceau in his book The initiatory gardens of the Château de Versailles.

At the centre of the pool, Latona and her children: Apollo and Diana. Latona, one of Jupiter?s wives, holds out her arm as if in supplication. The episode illustrated by this Fountain is taken from Ovid?s Metamorphoses. Walking with her children on Earth, where Juno, her official wife, has exiled her out of jealousy, Latona is surprised by nightfall in the village of Lycia. She asks the peasants to help her feed her children, but they turn away. As she cools off in the river, the peasants come and stir up the water with branches, raising the silt and preventing her from feeding her children. She implores Jupiter, who in response turns the peasants into toads and frogs.

The message here is threefold. On the surface, it symbolises the threat of what would happen to the courtiers if they ever thought of rebelling against royal power. It could also be seen as a call to change, to open up to others. But what is Latona really looking at from her vantage point in the East? Her son Apollo - incarnation of the sun, situated to the west in the basin in front of the Grand Canal? Or is it the Trianon, whose name evokes the Three Donkeys and which Hermetic philosophers can recognise from their research? The donkey was adopted by the alchemists as a symbol of raw matter?

The Apollo Basin

Tuby?s work was based on a drawing by Le Brun. Inspired by the legend of Apollo, god of the Sun and emblem of Louis XIV, it shows the god rising from the waves as if from a mirror, preparing to make his daily journey above the earth. He is seated on his phaeton, drawn by four spirited horses that he controls with just one hand, and surrounded by four tritons and four dolphins. At first glance, you might think that he symbolises the Sun as it sets off on its diurnal journey. But the sun moves from east to west. And here, it's facing east, towards the royal palace! So why is Apollo racing in the opposite direction? Could it be for aesthetic reasons that he has been installed this way? Or is he trying to guide us towards the realm of the gods, towards those who have absolute knowledge? It's up to you to find your own answer.

At Versailles, you have to see the visible and be sensitive to the invisible. Gently immerse yourself in it. Give free rein to your emotions. Walk the gardens again and again, until you finally understand and feel. For those who can grasp it, the path of initiation is inscribed in the groves, the fountains, the paths and the mythological figures. Versailles is only as good as its invitation to travel.

Text and Photos Brigitte Postel

Read

The initiatory gardens of the Château de VersaillesJean Erceau, Thalia, 2008.

Versailles, from the gardens to elsewherele Testament secret de Louis XIV, Vincent Beurtheret, A.M.D.G. édition, 1996.