Table of Contents

Orthez, the former capital of Béarn, situated between Pau and Bayonne, doesn't immediately reveal itself to the hurried visitor. Follow in the footsteps of its past for a summer "robinsonnade" with concerts at the Château Moncade.

The Pont Vieux, which spans the Gave de Pau, is the first stop. This medieval structure, 400 metres long, was for a long time a vital artery between the north and south of the Pyrenees. It's easy to imagine the pilgrims on the way to Santiago de Compostela, the merchants and soldiers who crossed it, in the shade of its sturdy arches, under the watchful gaze of its guards.

Not far from there, the Tour Moncade stands proudly, a vestige of a time when Orthez was the capital of Béarn. This imposing keep is a reminder of the authority of the Count of Foix-Béarn, Gaston III known as Fébus (1343-1391) was a lord, strategist and poet whose fame spread far beyond the borders of his principality. His nickname, echoing his battle cry : "Febus aban" ("Fébus en avant"), and its mottos "Febus me fe" and "Toquey si goses " ("Touch it if you dare") still rings out like a magnificent challenge. Under his reign, in the 14th century, Orthez enjoyed prosperity and the political and cultural influence that the town still bears in its stones.

The Place Royale, now a discreet square, later saw the symbolic figures of Jeanne d'Albret, the " Queen Jeanne "(1528-1572), who turned Orthez into a bastion of the Protestant Reformation. Born on 16 November 1528 in Saint-Germain-en-Laye castle, died on 9 June 1572 in Paris, Jeanne was Queen of Navarre from 1555 until his death, under the name of Jeanne III. She played a crucial role in the religious and political configuration of Béarn. At the beginning of the religious wars, she separates from her husband Antoine de Bourbon, Duke of Vendôme, who joined the Catholic camp, and established the Calvinism in his lands, a choice that shaped the local identity.

Musée Jeanne d'Albret, mother ofHenri IV

Nestled in a former Renaissance dwelling built in the XV century and XVI century, the Jeanne d'Albret museum is dedicated to Protestantism in Béarn and evokes the courageous commitment of Protestants in the face of persecution. Its collections retrace 400 years of the history of Béarn, from the origins of the Reformation to the 20th century. The house is notable for its remarkable spiral staircase set in an octagonal turret linking the two main buildings that make up the house. The museum displays the documentary collection assembled since 1987 by the Centre d'étude du protestantisme béarnais (Centre for the Study of Protestantism in Béarn).

© Michèle Lasseur

As you stroll through the narrow streets, you see facades with shutters closed, inscriptions half effaced, bell towers that punctuate the day. The walk ends on the banks of the Gave, where the water flows unhurriedly, like the passage of time.

The Tour Moncade and Gaston Fébus, guardians of a glorious Béarn

This massive keep, built in the 14th century, is one of the last vestiges of a fortified castle that was once the seat of power in the Bearn region. Its square silhouette, with thick walls pierced by narrow loopholes, embodies both defensive power and political sovereignty.

Gaston Fébus, one of the most fascinating figures of the Middle Ages.

Fébus, (in ancient Greek, Φοῖβος / Phoíbos is the name of Apollo and means "brilliant"), was born on the eve of the 100 Years' War. But in 1331, no one could have imagined that this prince would turn the Pyrenees into one of the most peaceful and richest regions of these troubled times. A man of arms and letters, a shrewd strategist and an enlightened patron of the arts, Fébus was both warrior and poet, a lord of keen intellect whose legend has spread far beyond the Pyrenees.

Fébus, whose fame stems as much from his military campaigns as from his The Hunting Book, a treatise on venery that remains a masterpiece of medieval literature, succeeded in making his capital a place where art, diplomacy and power intertwined.

© Michèle Lasseur

Under his reign, from 1343 to 1391, Orthez became the capital of a small, quasi-independent state, combining military rigour with cultural flourishing. From the battlements of the Tour Moncade, then the heart of the fortress, it was possible to keep watch over the Gave valley, a lookout against invasions and a sentinel for domestic peace. Orthez, through the Tour Moncade, became a centre of influence in troubled times, a bastion of civilisation on the Pyrenean border.

The Tour Moncade is open to visitors, but its silence remains steeped in history. From the top of its walls, the landscape is both modest and grandiose: the red roofs of the town are framed by the rolling hills of Béarn.

Here, suspended between heaven and earth, you can see how Orthez was a key player in a complex medieval chessboard, at a time when the King of France ruled over a small kingdom around Paris. The Tour Moncade remains the symbol of a fragile and tenacious power, of a local history that fascinates as much as that of the Plantagenets in Aquitaine.

Tour of the Moncade Tower in Orthez

As you pass through the low, austere entrance to the Tour Moncade, you are immediately struck by the freshness of the stone. The spiral staircase, carved into the wall, invites you to make a slow ascent. Each worn step bears the marks of countless feet, soldiers, lords and simple servants. You can imagine your footsteps echoing through this stone tunnel, the flickering light of a torch casting moving shadows.

Halfway up, a small opening - a loophole - lets in a trickle of bright light. Through this narrow hole, the archers watched over the valley, ready to defend the fortress against any intruders.

On the first floor, the vaulted room or Guards' Room opens onto a space where feudal councils were held. The rough stone walls are marked by the passage of time, while the small alcove niches would have been used to store parchments or precious objects. Here you can feel the discreet but constant presence of power, an authority that structured the life of the city.

Higher up, the main hall is where Gaston Fébus himself would have welcomed his visitors, churchmen, ambassadors and knights. You can almost hear the rustling of heavy cloaks and the clanking of swords laid down with respect. A monumental fireplace, now empty, is a reminder of the fires that warmed up the Béarn winters. Finally, the terrace offre a striking panorama: the Gave de Pau winds in the distance, bordered by gentle hills, under a vast sky. The wind plays in the battlements. From this balcony dating back to the Middle Ages, you can better understand the strategic and symbolic role of the Tour Moncade.

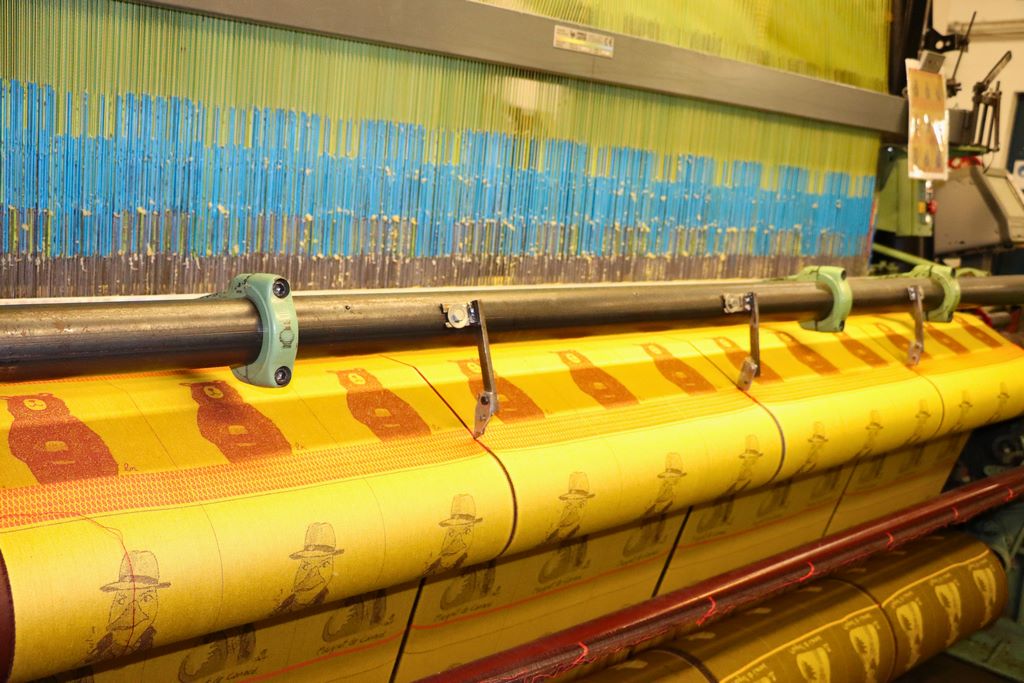

The loom, the beating heart of the Moutet weaving house

In Orthez, there's a house whose century-old walls resonate not with echoes of war or theology, but with a different kind of battle: that of craftsmanship, a taste for beauty, loyalty to a gesture handed down. Since 1874, the Moutet factory has been weaving more than just linen: it has been weaving a part of the identity of the Béarn region.

In this family-run business, linen, cotton and mestizo are more than just raw materials: they are the very stuff of memory. In 1874, Jean-Baptiste Moutet bought the shop "Around the corner" in Orthez. His son Georges specialised in table linen. At a time when the French textile industry was running out of steam in the face of globalisation, Moutet chose the narrow but straight path of quality, creation and loyalty to the Jacquard looms.

These looms, imposing, noisy, almost alive, perpetuate almost forgotten gestures. Here, each motif has its own language, each thread its own function. Traditional South-Western motifs - espadrilles, Espelette peppers, market scenes - coexist with contemporary creations, often the result of collaborations with artists. This dialogue between past and present, between domestic utility and aesthetic demands, is at the heart of the Moutet spirit.

Time seems to stand still in the workshop. It's like entering a cloister of work well done. There is something monastic about the regularity of the beating of the looms, the attention paid to tiny defects, the repetition of the gesture. And yet there's no lack of daring: the company has managed to open up internationally, supplying major houses and museums, without ever renouncing its origins in Orozez.

It's a form of resistance, gentle but determined, that would make Gaston Fébus or Jeanne d'Albret smile: that of a craft that never wanted to die, even when everything was pushing it to. Les Tissus Moutet is not just a business, it's a living archive, a tapestry in motion, which reflects Béarn's taste for useful beauty and loyalty to its roots.

In the workshop at Maison Moutet, a few steps from the Gave, the machines rumble, hiss, vibrate - and yet they speak softly. They are Jacquard looms, steel and wood machines born of an invention in the early 19th century, but which here in Orthez find their full expression in a companionship between man and mechanics. Bobbins stretched like the strings of an instrument, levers that click, a ballet of threads that rise and fall, crossing the weft to the rhythm of a repetitive mechanism. Rigorous logic and the art of detail. Because in weaving, every thread counts, and an error of a millimetre can distort the whole composition.

The warp, these threads stretched lengthwise, awaits the weft, which will be inserted perpendicularly, guided by the shuttle or, more often today, by a precise electronic system. Jacquard, a discreet genius, allows each warp thread to be lifted individually, creating incredibly fine patterns in the fabric. It was Jacquard that gave Moutet his geometric arabesques, chiselled typography and stylised landscapes.

But technique is not enough. You need the eye of the weaver. An irregularity, too much tension, a broken thread and the whole harmony wavers. The gesture is ancient, but never routine. With each roll, each design, you have to adapt, observe and correct. The craftsman then becomes the conductor of a ballet of a thousand arms.

Then comes the finishing: washing, ironing, cutting, hemming. Once again, everything is checked, ironed and inspected. Before becoming a kitchen towel, a tablecloth on a terrace, or a wall star in an architect's house, Moutet linen has gone through this slow process of care, patience and repetition.

The beret: the discreet flag of a province

At first glance, it's just a piece of felted wool, round and supple, with no visible seams. And yet, in the rugged silence of the Béarn valleys and in the hustle and bustle of public squares, the beret is a standard. It is, you might say, the discreet flag of a country that has never needed to raise its voice to affirm what it is.

Although the beret is now worn by everyone - soldiers, artists, shepherds and tourists - it was born here, in the Pyrenean foothills, and more specifically in Béarn, a region of hills and freshwater. For a long time, it was made at home, but its production was codified from the 19th century onwards, when the first mechanised workshops were set up in Nay, Oloron-Sainte-Marie and around Orthez.

But its history goes back much further.

The béarnais shepherd, an austere and sovereign figure, was perhaps its first ambassador. His beret - large, black, waterproof, sometimes embellished with a woollen star or a coloured thread - protected him from the rain, the sun and the gaze of others. It was a tool, an adornment and a marker of identity. You could read your age, where you came from, and sometimes even your political views.

The making of a beret requires a rare level of precision. In their shop, La Manufacture de bérets, right in the centre of Orthez, Sarah and Léa take care of all the production, from the unbleached yarn of pure merino wool to the finished product. It all starts with the circular stitch, knitted flat, before being pressed, i.e. felted, in hot soapy water. This process tightens the wool fibres to create a dense, almost waterproof étoffe that is both supple and resistant. Then comes the dressing process, where the beret is stretched, shaped and flattened. All this is done with the greatest respect for an ancient skill, often passed down from mother to son or from worker to journeyman.

The last houses, such as the famous Laulhère factory, continue this tradition with the elegance of an assumed loyalty. The beret, worn today by fashion designers and peasants alike, retains the ambiguity typical of truly popular objects: it is both from here and there, old and timeless.

In Orthez, it's not unusual to come across men, some of them very old, who wear it casually, like a second skin. They don't do it out of folklore, but out of custom. The beret is not a costume: it's a way of standing up to bad weather and oblivion. And perhaps that's what we've been weaving and coiffing in Béarn for centuries, this living, modest memory, worn on the front.

www.manufacturedeberets.fr

Getting there

Orthez, the medieval town and Château Moncade

Information and booking on 05 59 12 30 40

Meet at the Tourist Office.

Acknowledgements Nicole Magescas and guide Cécilia.

Individual guided tours of the city from May to October

e-mail : contact@coeurdebearn.com

www.coeurdebearn.com

Accommodation

Le Grand Houx : bed and breakfast

Marielle, Philippe and... their dog Looping welcome you to a large 18th-century town house (with the charm of the past, with creaking floors, but all contemporary comforts).

80 rue St-Gilles, 64300 Orthez.

www.legrandhoux.com

© Michèle Lasseur

Read

Gaston Fébus, Prince of the Pyrenees

Pierre Tucoo-Chala

Editions Deucalion, 1991.

Sotheby's organised an auction in Monaco on 23/2 and 1/3/87, the dispersal of the collection of the bibliophile Marcel Jeanson, who owned 5 manuscripts of the Treaty of Fébus. They fetched extraordinary prices: 2,600,000 and 6,200,000 francs.

Text : Michèle Lasseur