It is at the heart of the " terra quente The Foz Côa archaeological park, the largest known complex of cave paintings dating from the Upper Palaeolithic, is located in the "warm lands" of the Upper Douro.

This region, inhabited since the Lower Palaeolithic, was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1998.

In an area of 200 hectares, around the last 17 kilometres of the River Côa and the banks of the confluence with the Douro, more than 800 rocks bear the traces of the creative genius of the men who left their mark on these areas from the Upper Palaeolithic (25,000 years ago) to the present day, with more than 5,000 figures already inventoried. These schistose rocks, with their large vertical surfaces, served as a showcase for these early artists, and the sparse vegetation cover makes it easy to get close to them.

Revealed by a dam project

In 1989, an environmental impact study was carried out in collaboration with Professor Francisco Sande Lemos of the Archaeology Unit at the University of Minho. The study identified six prehistoric rock art sites, four of which were paintings, while the others revealed engravings from recent prehistory and Protohistory. This discovery has not prevented work on the dam from continuing. But the Portuguese Institute for Architectural and Archaeological Heritage commissioned a young archaeologist, Nelson Rebanda, to study the site in greater depth. And it was in 1992 that the first zoomorphic figures of the epipaleolithic type were discovered. Vale de Moinhos and clearly Palaeolithic engravings have been identified at the site of Canada do Inferno. In 1993 and 1994, with low water levels, other groups of Palaeolithic engravings were discovered. When these discoveries were made public, scientists and Portuguese public opinion, backed by the international press, cried scandal and did their utmost to save these discoveries. Building the dam meant drowning this archaeological treasure forever. Recognition of the cultural interest won out in 1995, when construction work was definitively halted. And in December 1998, the engravings in the Côa valley were recognised as part of humanity's cultural heritage by UNESCO.

Canada do Inferno

The valley of hell. "Hell is the heat here in the summer: over 45°C," jokes Luis Luis, an archaeologist with the Parque Archeólogico do Vale de Côa (PAVC). And the cold, dry winters, which dry up most of the Douro?s tributaries from July onwards. It was in this area that work on the dam began. A small reservoir remains, downstream of the confluence of the Douro and Côa rivers, which nevertheless flooded 80 % of the engraved rocks. The debate continues as to whether or not it should be destroyed or a tunnel dug to lower the water level. But the political will isn?t there. "When the water level is low, you notice that many of the engravings are now covered by silt," laments Luis.

Among the Palaeolithic engravings still visible are large wild herbivores that lived in the region: aurochs, horses, deer and ibex.

But what is typical of the Côa are the superimpositions of engravings created by generations of artists. "At Fariseu - a site currently closed to the public - we found a panel with more than 90 superimpositions: pitted, grooved, etc." continues our guide. He adds: "This is a major site because it was here that, for the first time, it was possible to archaeologically date Palaeolithic cave art".

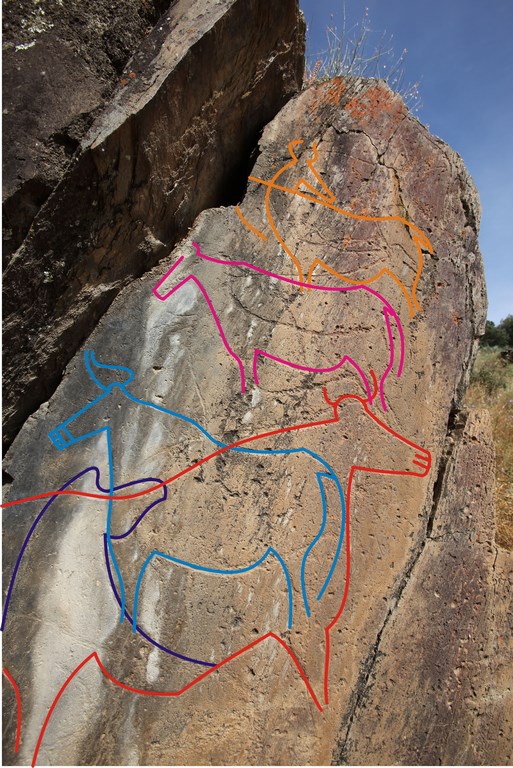

La roche, known as n° 1 , brings together the different techniques used by the artists: fine incisions, staking and grooving. The richness of this palette and the very nature of the support - vertical slabs of smooth schist - produce figures of astonishing expressivity.

Penascosa

At this other site, which is only visited in the afternoon because of the exhibition, the first panel found is panel no. 3, "very typical of the early Palaeolithic phase of the Côa, the Solutrean engraving phase", explains Luis. The rock is decorated with 12 superimposed animal figures, in particular aurochs, the upturned head of a horse and an ibex in profile, whose head seems to be looking straight at us. "What is astonishing is to see that some surfaces are not engraved and that others are filled with animals. We wonder about the significance of this choice. The fact remains that, as the ethnologist and archaeologist André Leroi-Gourhan said about cave art, superimposition is a real composition. Here we have three aurochs to the left and three ibexes to the right, and that's probably not by chance". As with the auroch on rock no. 3, the fluidity of the line allows us to retranscribe the details of the posture and the carriage of the horns.

Among the other panels on this site, rock no. 4 appears to depict a mating of horses. The mare is outlined with a fine groove, while the stallion above her is roughly pitted. Her head is carved in three different positions to suggest movement. Very few other representations of animals with several heads are known from this period, except in the Pyrenees and one in Libya, in the Akakus massif, carved in a rock shelter and dated to around 10,000 years ago. "This is the invention of animation," says Luis. "More than 10,000 years ago, these men represented the decomposition of movement.

Ribeira de Piscos

The third site we visit runs alongside the Piscos, a small tributary of the Côa. It's a very pleasant 3 or 4 kilometre walk along the stream, disturbed only by otters diving. It was here that one of the rare anthropomorphic figures of a man known as the "Piscos man" was spotted, his body depicted naked with an ejaculating penis. It was the night-time surveys that made it possible to spot this figure, made by very fine incisions that are difficult to see in daylight.

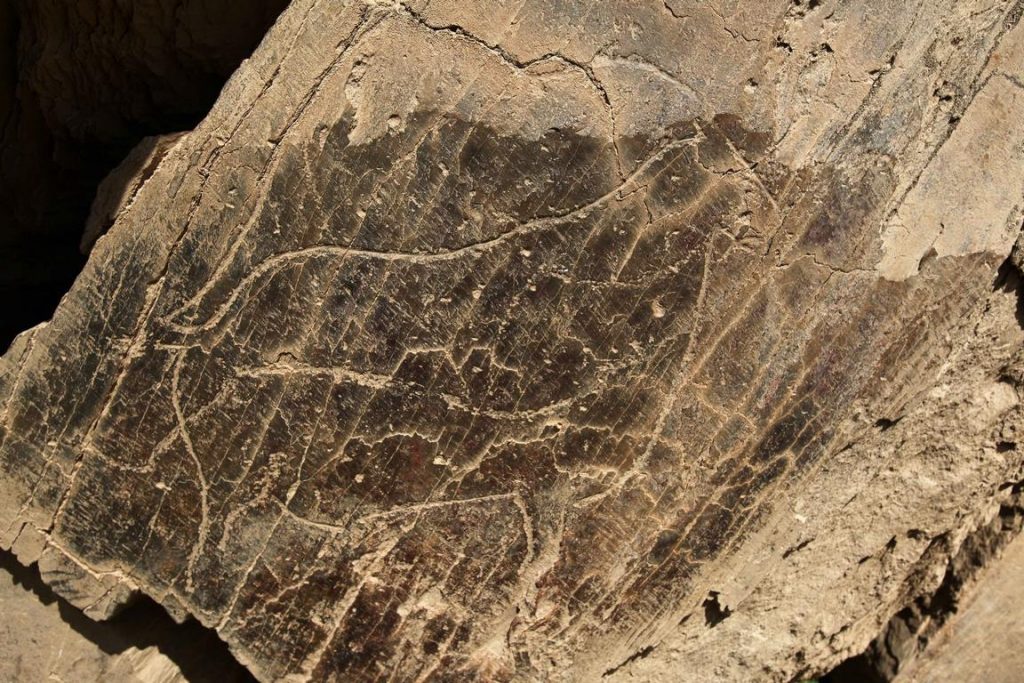

The engravings, which are mainly filiform, are more scattered along the slopes of the hill and are more difficult to understand. However, it is perhaps here, on rock no. 1, that we come across a masterpiece of Palaeolithic art. One scene depicts two horses crossing their heads and stroking each other, one of them only suggested. This

This attitude is typical of these animals and shows that the sculptor has a good knowledge of the social habits of horses.

It?s hard to speak of abstraction, but there?s a great strength in this very ethereal figure with its disturbing aestheticism.

Also worth noting on rock no. 13 are three large aurochs that were "no doubt made to be seen from the other side of the Côa", notes Luis.

"The discovery of the art of Côa reveals that the art of our ancestors was not limited to the walls of caves, contrary to what was thought last century. In fact, most Palaeolithic groups expressed themselves in the open air, and cave art must have been an exception," concludes Luis Luis.

Techniques for representing rock engravings

Palaeolithic art is presented in three technical forms: painting, engraving and bas-reliefs. Here in the Côa valley, painting has not withstood the ravages of time, as the supports are in the open air (apart from rare representations, including one of a man with his arms raised, dating from the Neolithic period). And there are no bas-reliefs on the site. But the use of vertical rock surfaces has enabled the engravings to reach us and to withstand the elements better than flat surfaces.

The techniques used by these Palaeolithic hunter-gatherers are of four kinds:

Fine filiform incisions are the dominant form (55 %). They are made by passing a small stone, "probably a flint or quartz chisel", explains Luis, which leaves a single fine line or clusters of parallel lines if there have been several passes. These incisions are very difficult to see, except in low-angled light. This is also one of the reasons why this site was not discovered earlier. The flint comes from places more than 250 km from the valley and from opposite sides, which shows the exchanges that existed between Palaeolithic groups. "Perhaps art had something to do with these exchanges," says Luis.

Staking was found in 25 % of cases. The stakes were made with a pick with a triangular head made of quartzite, a hard stone of local origin. Some of these were found at an occupation site at Olga Grande, under Gravettian layers in an encampment. This site is located on the other side of the River Côa, on the plateau. The picks have been dated by thermoluminescence to around 28,500 years ago, which archaeologists believe could date the Côa graphic period back to the Gravettian culture. The engravings are clearly visible. The lines are wide and deep, with a succession of irregular triangular impacts.

Less significant in number of representations than the previous ones, grooving is produced with a stone tool moved back and forth and which, in the end, will trace a regular line in the rock in the shape of a V or a U by abrading the rock.

These three techniques are often combined in the same figure," explains Luis. The artist can sketch the engraving by incision, enlarge it by staking and regularise it by abrasion", Luis points out. But there are also figures that use only fine incisions. A stylistic choice?

The last technique encountered, but much less common, is scraping, which involves wearing away a surface to create a chromatic contrast with the raw rock. This technique has been found at the Penascosa site in particular.

Advice

The Foz Côa archaeological park is less than 3 hours' drive from Porto. Not all the features at Côa date from the Upper Palaeolithic. Some groups or panels were created later (Neolithic, Iron Age, up to the beginning of the modern era). Visitors currently have access to three sites: Canada do Inferno, Penascosa and Ribeira de Piscos. It takes about a day and a half to visit all three sites. Visits can be made in the morning or afternoon, depending on sun exposure. These sites are guarded day and night and can only be accessed by registering with the Park. The other sites are not open to the public for study and conservation reasons. All visits are accompanied by a park guide who takes visitors by 4×4 to get as close as possible to the sites. Many of the sites are still privately owned. A programme for the public acquisition of archaeological sites is currently underway. A museum was also opened in July 2010.

Parque Archeólogico do Vale de Côa

https://www.arte-coa.pt/

Text and Photos (unless otherwise stated) : Brigitte Postel

Nice article, well written.