In Deauville, in the magnificent Franciscan convent, a remarkable exhibition brings together thirty years of creative work by the immense painter Zao Wou-Ki (1920-2013).

The exhibition, entitled "The alleys of another world", reveals for the first time the amplitude of the techniques of this "artist of the breath", which in Chinese cosmology animates the visible as well as the invisible. The creative intention of Zao Wou-Ki is, in his own words, to "open the door to another world". In this way, the Master has succeeded in combining the very different cultural traditions of China and the West in a variety of media, including paintings, watercolours, inks, prints, tapestries, porcelain, steles, ceramics and an imposing mural over sixteen metres long, commissioned by the architect Roger Taillibert in 1979 for the secondary school in La Seyne-sur-Mer.

Most of the works in this exhibition were produced between 1980 and 2010. They testify to the depth of his creative approach and are displayed on the walls in dialogue with quotations from his work. Self-portrait (1) and extracts from his unpublished translation of the Taoist treatise by Lao Zi (Lao Tzu), the Daodejing (Tao Te King) or Book of the Way and of Virtue.

Two artistic traditions

Born in 1920 in Beijing into a family of intellectuals from the ancient Song dynasty, the young Wou-Ki studied calligraphy with his grandfather and painting from an early age. At the age of 15, he entered the Hangzhou School of Fine Arts, where for 6 years he received a solid training, alternating traditional Chinese painting - calligraphy, landscape painting - and Western practices - classical drawing from live models, oil painting, watercolour, etc. He soon broke away from the imposed curriculum and opted for oil painting. At the time, he was particularly influenced by Cézanne, Matisse, Picasso and Chagall, whom he discovered through illustrations in Western magazines and postcards of Paris brought back by his uncle. From 1941 to 1947, he taught at the school where he had studied, before deciding to continue his artistic training in Paris for two years. Arriving in France in 1948, he settled in Montparnasse and joined the Nouvelle Ecole de Paris. His stay in France soon turned into a period of exile in 1949, when Mao Zedong came to power. This marked the beginning of a life of encounters and work.

A taste for colour

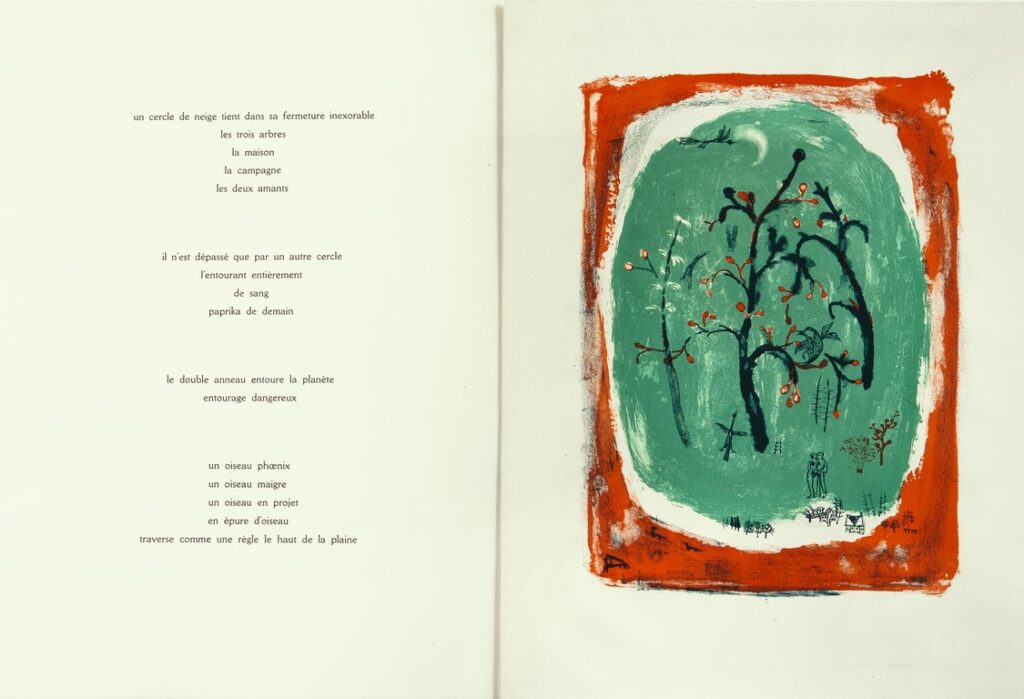

Figuration disappeared from his paintings, replaced by large, colourful spaces. This particularity was to help him emerge in the Parisian art world. In 1949, the Greuze gallery offered him his first exhibition, followed by La Hune in 1950 and a contract with the Pierre gallery the following year. From 1950 onwards, he turned to lithography, to which he added colour. His first eight Paris lithographs were presented to Henri Michaux (1899 - 1984), who wrote a poem for each one. This marked the beginning of an unfailing friendship with the poet, who was the first to recognise and value his talent. "This meeting was decisive because Michaux's attention to my work gave me confidence", he says. Poetry, a major literary genre in Chinese civilisation, is so close to painting in this tradition! The same instrument: the brush, and the same medium: ink. "I have always appreciated silence in poetry as well as in painting. In traditional Chinese poetry, there are always silences. If we respect silence, painting and poetry become much more alive. (2) Ezra Pound, Yves Bonnefoy, René Char, Claude Roy, and many others whose collections will be illuminated by Zao Wou-Ki's drypoints and etchings.

Making the invisible visible

A neighbour of Alberto Giacometti for almost ten years, he became a close friend. He also became close to the painter Jean Dubuffet. His discovery of the work of Paul Klee in 1951 was to play an important role in his career, pushing him towards lyrical abstraction, a movement characterised by improvisation, spontaneity of gesture and the emotion of the moment. From this date onwards, he left pure figuration behind and moved towards allegory. From 1953, the painter banished all explicit reference to reality from his work and returned to the sources of calligraphy, which he combined with abstraction. The discovery of the New York School and the contribution of the traditional Chinese ink technique enriched his hybrid universe, developing a painting that was always on the border between figuration and abstraction, between East and West.

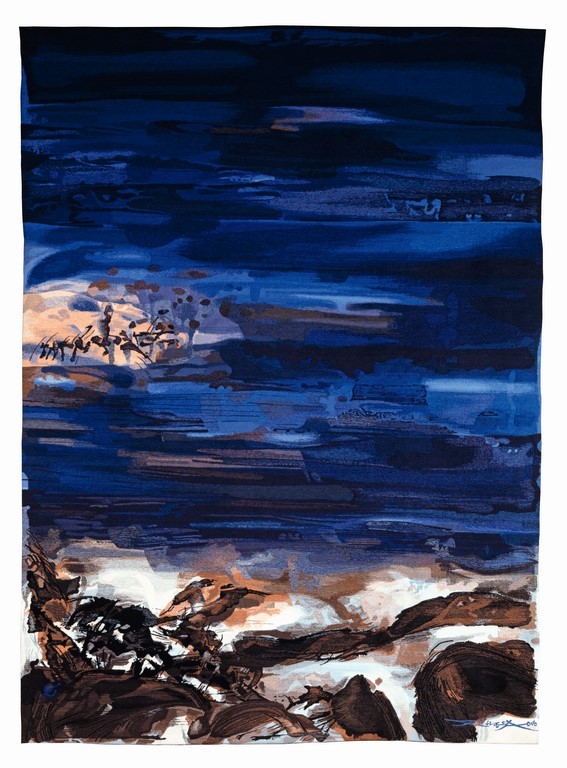

Following the example of Paul Klee, Zao Wou-Ki incorporated invented signs based on archaic Chinese characters into his works. The 1960s were characterised by a style that was both tormented and paradoxically controlled. From the 1970s onwards, on the advice of his friend Henri Michaux, he returned to the Indian ink technique, with large, glowing compositions streaked with black.

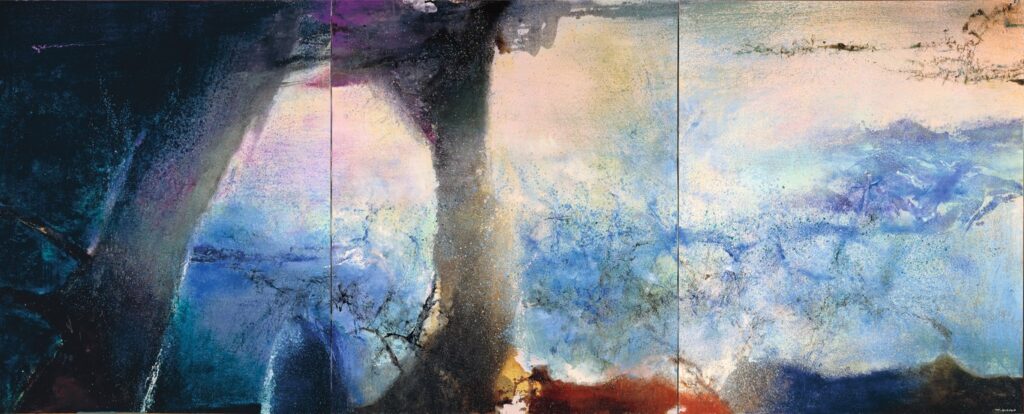

Following the death of his second wife May, Zao Wou-Ki returned to China in March 1972, reuniting with his family for the first time since 1948. It was then that he reconnected with his roots. Back in Paris, he met the woman who was to become his wife in 1977 and bring him happiness and serenity, Françoise Marquet, curator of the Paris Museum of Modern Art. His painting became more diluted and emptiness took centre stage. His new studio in the barn of his country house in the Loiret enabled him to paint large formats and above all imposing triptychs throughout the 1980s and 1990s. These were pictorial tributes to Claude Monet, Cézanne, Jean-Paul Riopelle and others. Not forgetting the sumptuous triptych dedicated to his wife, in shades of red, pink and mauve. Red, the colour of love, "the noblest colour" according to this artist who believed in the power of painting to capture the essence of the world.

An open scenography echoing the artistic freedom of Zao Wou-Ki

The museum tour, designed by Flavio Bonuccelli, begins with a painting suggesting the emergence of life and lithographs that freely refer to the four elements. Visitors are immediately immersed in the artist's dreamlike, lyrical compositions, which transcend the world of appearances and convey the impermanence of things.

Hanging in the central hearth, lit by the zenithal light of his Paris studio after 1959, the triptych Hommage à Claude Monet expresses the admiration he felt for the Master of the Water Lilies. "Zao Wou-Ki used to say that to paint, you have to look at other people's paintings. And one of the paintings he looked at a lot was by Monet. And in this painting, which is a tribute to Claude Monet, he is really rooted in Impressionism. He himself said that he wanted to paint space, light and movement. These are all realities found in Monet's work", explains Gilles Chazal, curator of the exhibition, General Curator of Heritage and Honorary Director of the Petit Palais, the Fine Arts Museum of the City of Paris.

The sumptuous diptych Il ne fait jamais nuit (2005), which gave its name to the exhibition at the Hôtel de Caumont in 2021, reveals him tormented by questions of light, space and emptiness. "I paint my own life, but I also try to paint an invisible space: that of the dream, the place where we always feel in harmony, even in forms agitated by opposing forces".

Diversity of artistic expression

Visitors are free to wander back and forth between the works, discovering all aspects of Zao Wou-Ki's work as they go.

The artist boldly tackles new territories often considered secondary in the West, such as porcelain and tapestry. She has worked with the Sèvres and Bernardaud manufactures in Limoges (Hommage à Li Po - La Lune et l'Ombre, 2008, enamel on porcelain based on the original painted in 2005), and with the Gobelins manufactory (Tapisserie Composition 1982, tapisserie de lice, 2008). "Paint, paint, always paint. As well as possible, the empty and the full, the light and the dense, the living and the breathing " he says in his Self-Portrait.

Navigating freely between media in a swirl of matter and a symphony of colours, his work exalts the erasure of reality to enter a world of delicate energy. "I like meditative painting rather than striking painting", said Zao Wou-Ki.

And so, "the man from the double shore", as his friend the writer François Cheng called him, has built bridges between his native China and his chosen land, France, a union that celebrates this attention to breath, silence and emptiness, in a luminous work that has never ceased to renew itself.

1 - Autoportrait, Zao Wou-Ki and Françoise Marquet, Paris, Fayard, 1988.

2 - Zao Wou-Ki, Couleurs et mots, interview, Paris, Le Cherche Midi, 2013.

Text : Brigitte Postel

Photos : Brigitte Postel and see copyright

Photo opening : Dennis Bouchard

The exhibition Zao Wou-Ki - The alleys of another world can be seen at Franciscan Sisters of Deauville until 27 May. It is part of the Festival Impressionist Normandy which runs from 22 March to 22 September to mark the 150th anniversary of Impressionism.