From time immemorial, people have sought answers to the question of their origin and destiny. Each culture has its own predominant narrative about the world. So, wherever we live, we inherit these narratives with which we all forge our identities. What do these narratives tell us? Do they have common origins? Are there universal myths?

Interview with Jean-Loïc Le Quellec, anthropologist, mythologist and prehistorian, known for his work on the rock art of the Sahara, and Professor at the Centre d?études des Mondes africains (CNRS) and Honorary Fellow, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg (South Africa).

You took an interest in the oral traditions of the French regions, then Quebec, Libya and Ethiopia, before extending your research into comparative mythology to the whole world. What do these myths teach us?

A myth is literally a story (from the Greek ????? muthos speech, words). It belongs to narrative folklore and generally concerns events in a time that is inaccessible to humans; this is the case, for example, with stories about the origin of the world or of a people. Anthropogonic myths explain the origin of humans, while cosmogonic myths explain the origin of the world. In a way, they all answer the questions that children ask themselves: why does the world exist, why and how did man appear on earth? These myths are logically structured: for humans to exist, a world must first come into being, either spontaneously or under the impetus of primordial beings (supernatural entities or forces, gods, heroes, demiurges, etc.) responsible for creating it from the void, from an original nothingness or from initial chaos. An initial state of the world is thus presented. Then an event occurs that creates a rupture between this old world and the next, and this is what the myth explains.

In Africa, for example, there are three main types of cosmogony, depending on whether the world is uncreated, the result of a god?s act of creation (Immana of the Rwandans, Amma of the Dogons in Mali, etc.) or the result of the self-creation of an original void. - or whether it results from the self-creation of an original void: the Bambara cosmogony postulates the existence of an original void called ? gla from which emerged a voice, the verb, which, in expressing its intention to create, produced its double and united with it). More generally, there are two types of cosmogony. Either they go hand in hand with theogony, where the phases of genesis are linked to successive generations of divinities (Mesopotamia, Greece, ancient Egypt, etc.), or the creator precedes his creation, as is the case in biblical Genesis.

However, not all mythologies include cosmogonic myths. In China, for example, there is no genesis until the first century, and in Australia, the stories say that "in the Dreamtime", mythical beings wandered into a world that was already there, shaping the landscape to prepare it for the emergence of man. These are myths of peregrination, and the course of these itineraries is preserved in memory. What is interesting about all these stories is that they tell us more about humanity and ourselves than they do about what they claim to elucidate, namely the origin of the world.

What are the other types of myth?

First of all, there are the ethnogonic myths that explain how peoples have differentiated themselves. This is often a way of justifying the dissimilarity between one?s own group and its neighbours. These narratives, which aim to account for cultural diversity and linguistic differentiation, are often combined with those of dispersion to form a whole that explains how the earth was populated. Among these are the Flood myths, which are widespread throughout the world and tell us that it was the second humanity that populated the globe because, it is often said, the first was so bad that it had to be destroyed by water? or by fire, according to other variants. Myths of the Tower of Babel type, widespread in America, Asia and Africa, describe the dispersion of peoples, then the diversification of their languages to punish them for their attempt to reach the heavens by building a gigantic tower or similar structure, which was destroyed.

There are also sociogonic myths that explain the origins of societies and social classes. In Peru, for example, it was said that three eggs fell from the sky. The first, made of gold, gave birth to the officials; the second, made of silver, to the warriors; and the third, made of copper, to the lower classes.

What methods do you use to study these stories?

Countless stories of this type have been collected around the world, and the challenge is to study them scientifically. In other words, the aim is to develop theories that can be verified, or challenged with rational arguments, however difficult this may be. Many specialists have gradually built up a science of mythology with its own methods of approach, proceeding in particular by comparison, to try to see if this or that myth has a common ancestor, if we can identify an area of the world in which it was born, and so on. These stories can be transcribed, examined and compared. We can also write their history. When does a story appear? Were there any influences? Can you spot any borrowings from earlier or neighbouring stories? Quite often, if you proceed in this way, you will be surprised to find similarities in detail or overall between stories from very different places, and you can then map them out. If we compare certain myths by trimming away the details, putting aside the names of the heroes, heroines, gods, etc., we notice that they may have the same skeleton, but that in one of them the story will take place during the day, while in the other it will be at night. Or the role played by a hero in one will be played by a heroine in the other. So each story inverts the other, and the inversion that enables them to be related is one of the concepts used to analyse myths. Another approach is areology, which involves studying the distribution of stories that are now widespread throughout the world. This sometimes makes it possible to reconstruct a large part of their prehistory and to find, behind the multiple forms of certain myths, a geographically coherent organisation that may bear witness to ancient migrations, some of which date back to the Palaeolithic period.

What are the main anthropogenic myths?

Anthropogonic myths, i.e. those that explain the origin of humanity, can be grouped into a dozen categories, which vary greatly in frequency and distribution.

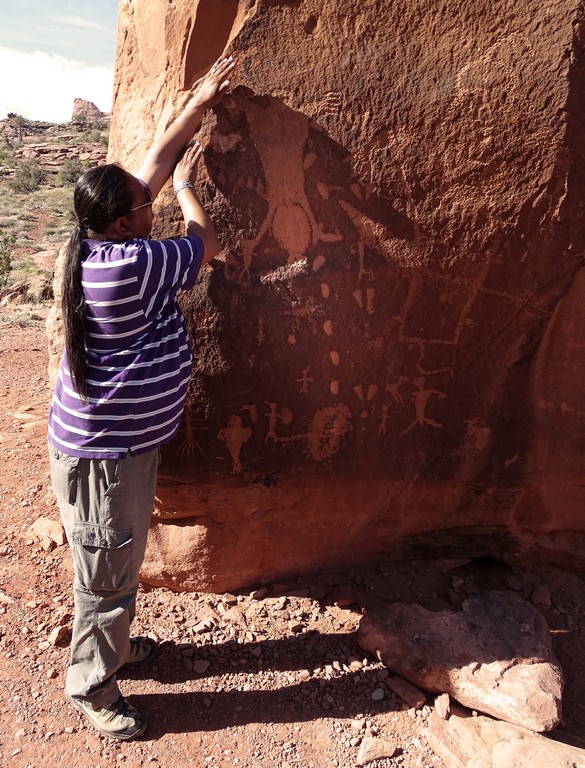

Among these stories, that of thePrimordial emergence is the most widespread of all those that ethnographers and travellers have been able to record. It tells of the emergence in this world of beings who already existed in another and who are of chthonic origin, i.e. subterranean. They came to the surface through a hole in the ground, punctured by a guide animal or tree, or through a cave from which the animals also came. Its widespread distribution suggests that it is one of the oldest known myths. In the Tsodilo Mountains region of Botswana, I was shown a hole in the ground and told that the first humans and animals once lived deep underground, but that one day they came out, and as the rocks were still soft at the time, they retained their traces, which are still visible today. In North America, a Hopi friend told me virtually the same story to explain the origin of his people, and I was given a similar account on Jeju Island in Korea, where I was also shown the primordial emergence hole.

Born in Africa, this myth of Emergence spread around the world at the same time as the anatomically modern humans who left the continent in the Palaeolithic. This exit did not happen all at once. It is thought that several small groups left at different times, with their own myths, languages and customs, to reach the Cantabrian peninsula around 45,000 years ago. This story therefore formed an essential part of the ontology of the artists who, in the Final Palaeolithic, entered the caves to paint or engrave images that perhaps ritually evoked it. In the end, it appears that, despite the diversity of its present-day variants, this story, which is part of the ongoing adventure of humankind, accompanied our ancestors for dozens of millennia? and that it is still being told today!

What are the other myths about the origins of humanity?

One of these origins is celestial. In this case, it is said that humans one day fell from the heavens, or that they descended by rope, ladder, vine or spider's thread. The first humans can also be of animal origin, particularly when they are born from an egg, according to a common story told by the Dayan in Indonesia. Or they may have come from plants: among the Apinaye of the Brazilian Plateau, Sun and Moon, the first occupants of the Earth, planted squash and, when they were ripe, put them in the water under the small bridge that crossed the nearest stream, where they changed into human beings.

One popular etymology has Adam as "The Glebeous" or "The Glazy", since YHWH (the tetragrammaton for the Creator) fashioned man from dust taken from humus (Genesis 1, 26; 11, 7). This is an example of a myth of creation by coroplasty - a term taken from the name of the sculptors of female figures in clay, called coroplasts in ancient Greece (from the ancient Greek ????, kórê(meaning "young girl").

Another myth, widespread in the northern hemisphere, in both the Old and New Worlds, is that of the cosmogonic Diver, which appeared in Eurasia before spreading to North America. Rarer are the aquatic origins, the begetting of a primordial couple or the creation from divine scales.

This small number of types of anthropogonic myth, and the fact that their geographical distribution varies greatly from one type to another, makes it impossible to seek the origin of these stories in the individual psyche, and even less so in these hypothetical archetypes which, according to the psychiatrist Carl Gustav Jung, are likely to appear at any time, in any place, in any culture. A study of their distribution on maps is enough to convince us that this is not the case.

Are there universal myths?

Myths always tell the truth in the group that holds them as their founders, and yet, in their infinite variety, they differ profoundly from one another, which is why none of them can claim to hold a universal truth. From this point of view, for example, the biblical "genesis" is in no way different from the thousands of other stories about the origin of the world that can be found all over the world, and I see no objective reason to favour it over any other: there are Amerindian or Oceanic "geneses" that are just as rich and poetic.

Ideally, if we wanted to prove that a myth is universal, we would have to study all the world?s cultures and demonstrate that it is attested everywhere, including in all those that have disappeared. In practice, it is impossible to demonstrate such universality. In fact, it?s much simpler to find counter-examples. Rather than trying to demonstrate the universality of something, I'm going to look at places where it doesn't exist. Take the example of Mother Earth, which we consider to be so 'natural' that it seems universal. But whenever something seems 'natural' to you, tell yourself to be wary, because in this field, practically everything that seems 'natural' is actually cultural. In this example of Mother Earth, if we look at the mythology of Ancient Egypt, the deities of the earth and sky are called Geb and Nut. In the frescoes, the divinity representing the earth is lying down, and the celestial one is on top, forming a kind of bridge with her body. But it's THE earth, because it has a magnificent phallus raised towards the sky to impregnate THE sky! And it wasn't just the ancient Egyptians who saw the earth as masculine. In South-East Asia, among the Kachins, a well-studied population whose mythology we know well, it's the same thing: the Earth is also a masculine being! So we're back to Mother Earth as a universal archetype? We can follow the same approach for all the archetypes, and then we realise that there is no such thing as an "archetype". And that not everything that seems obvious to us is the truth.

You would like to introduce the study of mythology at school.

Yes. When a human group has an explanation of the world, it has no desire to change it and considers that its own view of the world is the best possible for the whole world: this is called ethnocentrism. However, it is only later, often by chance, by meeting other human groups that we can question our vision of the world and realise that our way of seeing the world is not the only one possible. By distancing ourselves from our own mythology in this way, we become much more serene, more able to examine the dissimilarities in the different narratives of the world and not condemn a priori any narrative that is different from our own. That's why I believe that teaching mythology to children would help to defuse conflicts that are based on different myths. Of course, science is of a different nature, but what unites us all is the need to tell something about the origin of the world and of human beings. The study of myths helps us to write the long adventure of a common humanity that passes them on again and again? if only for the pleasure of listening to a good story.

Interview by Brigitte Postel

Published in issue 5 of Natives, des Peuples, des Racines https://www.revue-natives.com/

Read

"L?Origine de l?humanité selon les mythes" Variations on the history of humanity. Preface by Yves Coppens, Paris: La Ville Brûle, 2018

"Dictionnaire critique de mythologie", co-authored with Bernard Sergent. CNRS Editions.

For children: "We are not at the centre of the world" Claire Cantais ? Jean Loïc Le Quellec. La Ville Brûle.